One Good Question with Mike DeGraff: Are Schools Destroying the Maker Movement?

This post is part of a series of interviews with international educators, policy makers, and leaders titled “One Good Question.” These interviews provide answers to my One Good Question and uncover new questions about education’s impact on the future.

“In what ways do our investments in education reveal our beliefs about the next generation’s role in the world?”’

There was a call for 100,000 STEM teachers in the US, and since then there have been tons of initiatives, and related funding, to respond to the need (some say too much). UTEACH is a very constructivist-oriented teacher education program for STEM teachers, that began at UT Austin and has spread across the country. Then we saw the launch of Maker Faire™ to showcase STEAM design in informal learning space. When I went to my first faire 3-4 years ago, I was amazed that there wasn’t tighter articulation between schools, teacher education programs, and what’s going on in this sector.

In schools, "making" is mostly robotics, especially at the secondary level. School libraries may have makerspaces that are more diverse, but there’s very little happening in teacher preparation for how we prepare teachers for these spaces that are proliferating. No two people have the same vision for what you mean when you say makerspace. Whenever you talk about this, it’s so easy to get excited about the 3D printer, laser cutter and other specific tools. At UTeach, we’re more interested in how it transforms what kids are able to do and how teachers are empowered to teach differently. Not to dismiss the tools, but ultimately, what’s so exciting about all of this stuff is how it connects to this lineage of progressive education dating back to Dewey and meaningful, authentic, relevant work. That’s what’s so powerful to me about this whole maker movement. It really champions student voice in a way that I don’t see in any other movement/innovation/fad. How can we replicate that for every kid? One of the biggest hurdles in education and industry is to get kids curious. Makerspaces can get them to a point where they can start wondering.

The maker world and project-based formal education don’t seem to respect each other enough. The maker world which is super auto-didactic, self-sufficient, diy, vibrant and very curious. The maker world sentiment is that schools are going to destroy the maker movement by embracing it and standardizing it. It’s not an unfounded fear. Look at the computer labs in the 90s. The way that education works is in compartmentalizing. My biggest fear is that it becomes a space where you go and do « making » for an hour completely separated from (or only superficially connected to) science, math, language arts, literature, art, etc.

The formal education world is coming from a perspective that we’ve been doing « making » well before Maker Faire started in 2006, but have called it other things like project-based instruction. Colleges of Education see the value in makerspaces, but in public education we have to focus on serving every kid. While the Maker Education Initiative motto is « every kid a maker » colleges of education and educators in general are asking what do we do with kids who aren’t motivated by blinking a light or don’t identify with the notion of making? How does PD play out in these different areas and what does it look like as these spaces develop?

“Do you think that schools/universities would be adopting Makers Spaces if it wasn’t tied to funding?”

These spaces have always existed in universities, but they used to be highly articulated with coursework. Making in a university is usually housed in the college of engineering, which makes sense for digital fabrication and electronics. You were typically a junior before you got to that level of coursework and only accessed the equipment for specific, course related projects. If you talk to industry, a big complaint is that universities are producing engineering graduates who can calculate, but can’t use a screwdriver and a hammer or connect that academic experience to the real world.

A makerspace is more similar to a library type model so it’s open and you can go in and make when/what you want. UT opened a Longhorn Maker Studio and when I went there in November it was full of kids making Christmas presents (like ornaments, a picture frame, and other highly personal artifacts). There’s a lot of class projects, but it’s more about figuring out what they can do with it. That’s what’s exciting.

Something that I see as very similar to the makerspace idea in the College of Science is open inquiry where students choose what they want to learn more about, design an experiment, and analyze results. In UTeach, one of the nine courses is totally dedicated to this process. Instructors have noticed that the hardest part of the process is to get students to become curious. Get students to develop their own questions that can be addressed by experiments. In education, we have identified content, but the gap is how we inspire students to be curious and engaged and motivated and passionate. It’s so well connected in general to how we get students to think and be self-motivated and have internal drive.

“One could argue that Makers spaces are going the way of MOOCs — only reinforcing the privilege and access of middle-class paradigms and still largely unused in lower-income/marginalized communities. If we really belief that Makers spaces improve creativity, critical thinking and STEM, what will it take for the movement to reach a more diverse audience?”

Why I see maker movement as being fundamentally different, is that I see it as hitting on different things, namely on student motivation and constructivist education, with what we know about how students learn best, project-based instruction, and the evolution of progressive education. At the UTeach conference last May, we had several sessions about making in the classroom. It’s important for us is to embed this into regular coursework. Right now, a lot of the robotics and electives are afterschool activities, but in order for this to be truly democratized, we have to make it part of our classes—science and math that every kid takes. NGSS and CCSS math standards demonstrate value for persistent problem solvers, design cycle and implementing inquiry. Makerspaces can support these standards for all students.

As part of the maker strand at our UTeach conference Leah Buechley gave the plenary talk contrasting mainstream maker approaches with tools and techniques designed to support diversity and equality.” This is exactly why we, in education, need to systematically develop opportunities around « making » for a more diverse population, which early indications show is working. We’re already seeing that the demographics of youth-serving maker spaces are much more diverse than that of Maker Faire.

Mike’s One Good Question: How can we use this space to address community needs ? What we’re doing is making things, but why are we making them?

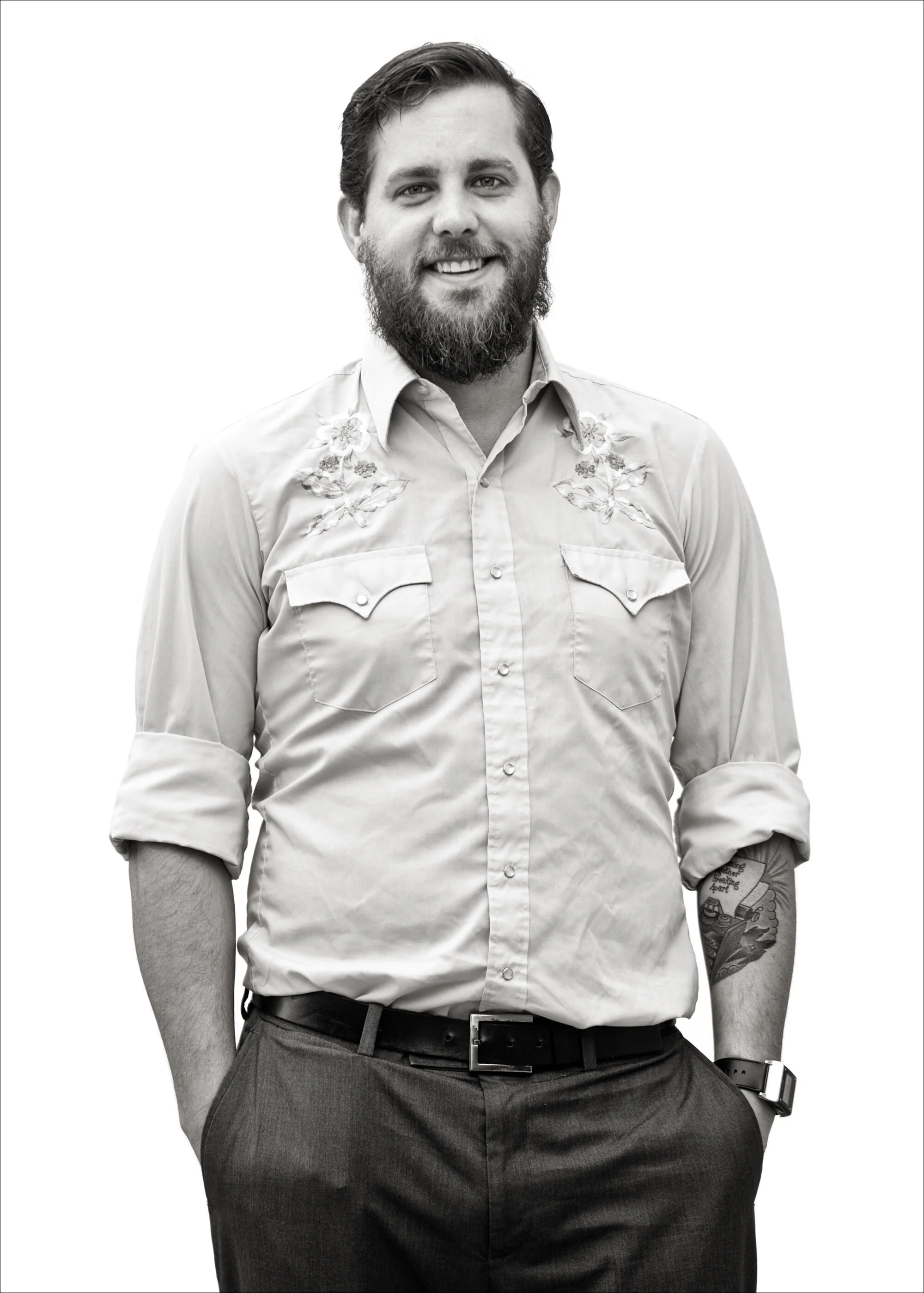

Michael DeGraff is the Instructional Program Coordinator at the UTeach Institute. His work includes coordinating the Instruction Program Review process for all UTeach Partner Sites as well as supporting instructors to implement the nine UTeach courses.Michael has been a part of UTeach since 2001, first as an undergraduate student at UT Austin (BA Mathematics with Secondary Teaching Option, 2005), then as a graduate student (MA Mathematics Education, 2007), and finally as a Master Teacher with UKanTeach at the University of Kansas. He was also instrumental in launching Austin Maker Education.