One Good Question

Blog Archives

One Good Question with Kaya Henderson: What Will Make My Heart Sing?

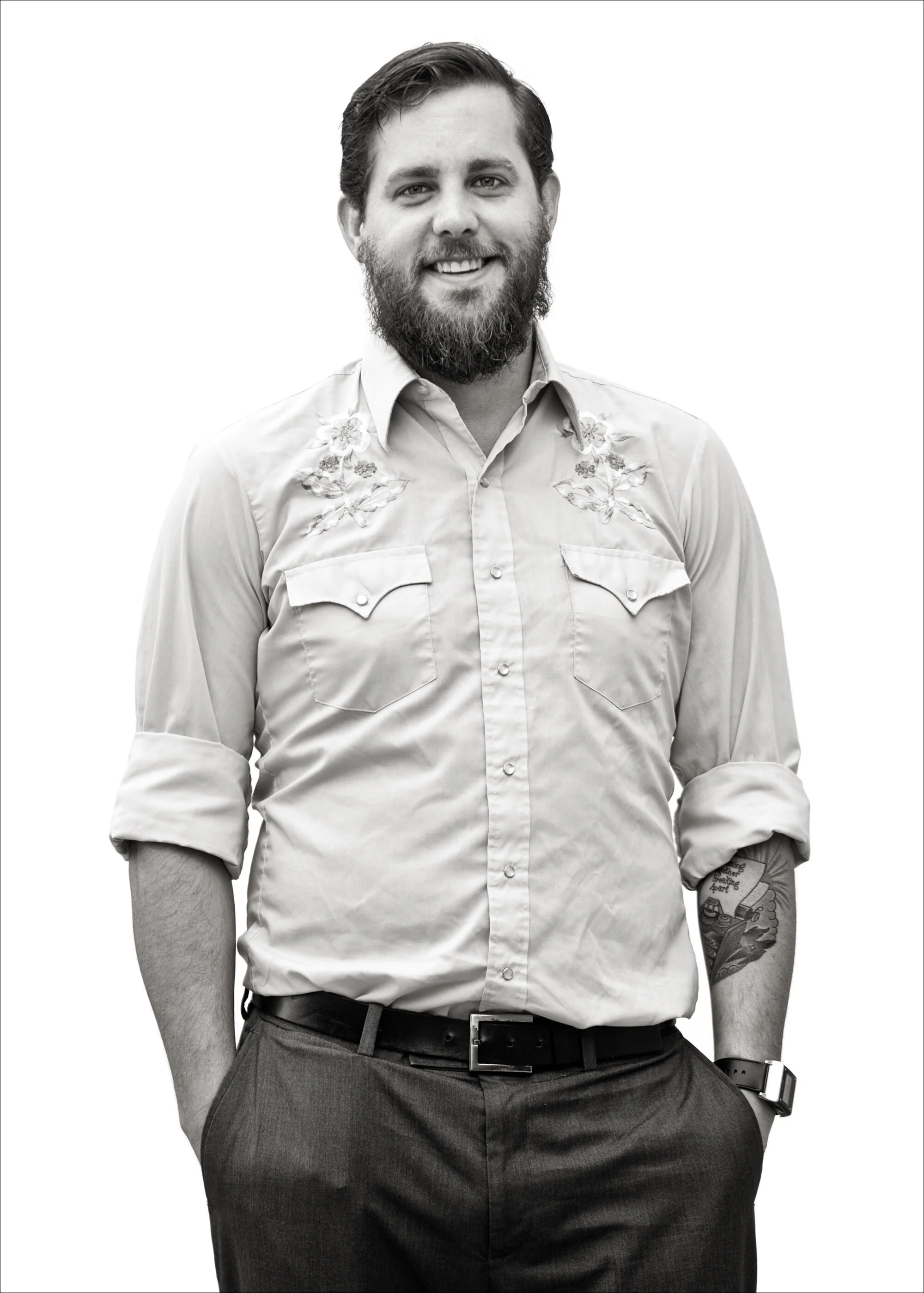

Kaya Henderson

This post is part of a series of interviews with international educators, policy makers, and leaders titled “One Good Question.” These interviews provide answers to my One Good Question and uncover new questions about education’s impact on the future.

“In what ways do our investments in education reveal our beliefs about the next generation’s role in the world?”

The US has invested in two things in public education that are fundamentally wrong. The first one? Perpetuating really low expectations for kids. When you look at our education investments over the last 20-30 years, the focus has been low-level proficiency in a handful of subject areas. That belies a fairly low expectation about what kids can accomplish. It reveals our belief that, if schools can just get the moderate level of proficiency, then they will have done their job. We seem believe that low to moderate proficiency is the goal for some kids. For wealthy kids, we believe they also need international trips, art and music, foreign language, and service experiences. Those investments, made both by wealthy families and wealthier schools – belie greater expectations for those students.

I had the very good fortune to grow up in a family that started out poor, but transcended to the middle class over the course of my childhood. I was blessed to have a mother who had us traveling the world, insured that I spoke a foreign language, took horseback riding, and participated in Girl Scouts. But I had cousins who came from the exact same place as I did, whose parents and schools didn’t share those expectations. Some of them attended the magnet elementary with me, so even when their parents didn’t have high expectations, good public schools put us on the same trajectory.

When I became chancellor of District of Columbia Public Schools (DCPS), my expectations were based on my personal experiences. I believe that schools have to inspire kids to greatness. What I saw however, was people trying to remediate kids to death. So, I inherited a district where people weren’t teaching social studies and science, and where arts and foreign language programs were paid for by some PTAs, because some parents recognized the needs even with the district didn’t. What I saw was different expectations for different kids, and the investments followed suit. Our goal was to recreate these rich experiences, both enrichment and academic, for all kids.

The second investment that cripple US education? Systems that are built for teachers who we don’t believe in. We try to teacher-proof the things that we want teachers to do. But, if what we give teachers is worthy of them, if it peaks their intellectual curiosity, makes them need to learn, pushes and challenges them? — then teachers rise to expectations in the same way that kids do.

One of the things that we did in DCPS was to significantly raise teachers’ salaries, and radically raise expectations. Lots of people were not happy about it, but the people who were happiest? Our best teachers! They were already rising to highest expectations.We reinvented our curriculum aligned to Common Core State Standards, with the idea that every single course should have lessons that blow kids’ minds. We designed these Cornerstone lessons – the lesson that kids will remember when they are grownups. For example, when we’re teaching volume in math, it coincides with a social studies unit on Third World development. So students learn to design a recyclable water bottle, in a few different dimensions, to help developing countries get better access to water. They then build the prototypes for the containers and test them out. Lessons like that make you remember volume in a different way.We wanted one Cornerstone less in each unit, for a total of five over the year. We designed lessons for every grade level, every subject area. When we designed the Cornerstones, we mandated that teachers teach that lesson. What happened? Everyone used them and demanded more! Teachers wanted to have 3 or 4 Cornerstone lessons for each of their units.

“How do we get parents to opt — in to public schools at scale?”

I had families tell me that I needed to do a better marketing job, that I wasn’t selling DCPS enough. They compared us to charter schools with glossy brochures. When I started, the product that we had to market wasn’t good enough. I didn’t want to duplicate the negative experiences parents were getting: great marketing, but then disappointment in the product.The first year that I was Chancellor at DCPS, we didn’t lose any kids to charters. That was monumental! After 40 consecutive years of enrollment decline, we had 5 consecutive years of enrollment growth. We laid a foundation with a good program, then we listened to parents. We combined what they wanted, with what we knew kids needed, and rebuilt the system from the ground up. Our competitive advantage is that we are not boutique schools. We are like Target: we have to serve lots of different people and give them different things. As a district, our challenge is to guarantee the same quality of product, regardless of location. What are we going to guarantee to every family and how will every family know that?

We started by re-engineering our elementary schools. Some schools had been operating for so long without social studies, that they didn’t know how to schedule for it. It meant creating sample schedules for them and hiring specialist teachers. Once we could tell parents that every school would have XYZ programs, they didn’t have to shop for it anymore! Then we moved on to middle school and guaranteed advanced and enrichment offerings at every campus. Then we did the same at the high school level and significantly expanded AP courses. Today all of our high schools offer on average 13 AP courses. Even if there are kids who have to take the AP course twice, they do it. We know that the exposure to that level of academic rigor prepares students for college.

DCPS was a district where families came for elementary, opted-out at middle school, and then maybe came back for a handful of high schools. So we looked at the boutique competitor schools and added a few of those models to DCPS too. You do have to sell, but there’s no better advertisement than parents saying “I love this school !” Some of our schools that were never in the lottery, now have a ton of applicants! We were careful not to build things on charismatic people, but to build systems so that these gains would be sustainable. Now parents that never would have considered DCPS are clamoring for our schools.

Kids are kids, no matter where in the country they live. The cost of education is static. If we are serious about this education, we have to make some different decisions and put the money behind it. We’ve seen ten consecutive years of financial surplus in DC, at a time when the country was falling apart. I was even more lucky that three different mayors prioritized education and but the money in the budget. You can’t expect schools to do the more on the same dollars. You have to invest in innovation funds.

Kaya’s One Good Question: Literally, my question is what is the best use of my time moving forward? When you’re running a district, you are in the weeds. You don’t know about all of the new and exciting things in the space. Right now, I’m being deliberate about exploring the sector and that’s important. I want to figure out what will make my heart sing!

Right now I’m obsessed with the intersectionality about housing, education, jobs and healthcare. This old trope that, if we just ‘fix’ education, is garbage. I’m not saying it’s linear or causal, but it’s necessary to work on more than one issue affecting families at a time, and the efforts have to be coordinated and triangulated. Some of the most exciting things on the horizon are people like Derwin Sisnett, who is working to re-engineer communities for housing to be anchored around high performing schools and the community is replete with healthcare services and job training that the community needs to improve.

Kaya Henderson is an educator, activist, and civil servant who served as Chancellor of the District of Columbia Public Schools from November 2010 to September 2016. She is the proud parent of a DCPS graduate and a DCPS fifth grader.In 1992, Henderson joined Teach For America, and took a job teaching in the South Bronx in New York City. Henderson was promoted to executive director of Teach for America in 1997, and relocated to Washington, D.C. In 2000, Henderson left Teach for America and joined the New Teacher Project as Vice President for Strategic Operations.

One Good Question with Ben Nelson: Do We Actually Believe that College Matters?

This post is part of a series of interviews with international educators, policy makers, and leaders titled “One Good Question.” These interviews provide answers to my One Good Question (outlined in About) and uncover new questions about education’s impact on the future.

“In what ways do our investments in education reveal our beliefs about the next generation’s role in the world?”

Education matters. It sounds so banal and simple. Everyone in the world says this, but I argue that no one actually believes that education matters. Here’s the proof:Imagine a high school student that has the option to go to A) Harvard or B) some other less prestigious educational institution where they will get a better education. How many people are going to say don’t go to Harvard? Effectively nobody.If people actually believed that education mattered, then college rankings, curricula, and choice wouldn’t exist in these formats. Fundamentally, no one believes that the education matters, but that the credentials matter. People think “have credential, will travel”. And they’re wrong. Credentials actually don’t really matter. Credentials ultimately are put to the test when you get to the real world. The investment – whether dollars, human capital, time and money—from government, private sector, or families—the investment that returns the most in your life is learning. It’s not getting an education.

“You’re shifting the whole paradigm here – learning matters but learning institutions less so? I still believe in "school," so help me understand this.”

We need to make a distinction between getting an education, being educated and actually learning. One of the key elements to know that learning has occurred is the concept called far transfer. Far transfer occurs when people apply learning from one context to a problem/need in a radically different context. You know that some has learned when they say, “I’ve never seen this before, but I’ve seen all of these common elements. I studied XYZ and there are patterns developed between them that I recognize here. With certainty, I know that if I do ABC I will likely get positive results.So for families wondering where to invest in their children’s success? Invest in education, not the credential.

“How do you get people to shift their values towards “education” not credential?”

Hyperbolic discounting is the phenomenon that things get better with age. Among youth and adults—if you are told “you can invest $10 today and get $100 5 years from now” most people say they would rather spend the $10 today. Similarly, when you tell an 18-year old kid, you shouldn’t drop acid/do coke, because you’re going to have a lot of fun tonight, but 10 years from now you may ruin your life. They discount it. This is so built in to human nature to think about short-term reward vs long-term benefit.

It’s hard to admit that you don’t believe in our education system. When push comes to shove and you’re at the supermarket, run into your old friend and she asks where your kid is going to school, you want to say Harvard (or whichever university has status for you). You don’t want to say she’s getting an amazing education at "unbranded institution." You sacrifice the future well-being of your child to have an easier supermarket conversation. That’s how human beings behave.

How do we have a republic that works? People understand and are informed instead of responding to their cognitive biases. They actually commit to spending the time thinking about how not to generate irrational biases. That requires long-term thinking, i.e. I’m going to spend more time pouring through this article, so that my one vote will be a beacon of light and influence others. We’re not built to think that way, even though we live in a world that requires us too. That’s the problem we’re stuck in. We’re not designed for the modern world. We’re still designed to be hunters and gatherers. The only solution I see to our problem is long-term and systemic. Minerva exists to reform education systems all over the world. We believe that reform occurs when the most prestigious institutions reset. Ripple effect goes through the rest of the system. This is a process that will take longer than my lifetime.

Don’t divorce the election outcomes from what government policy has been over the past several decades. Republicans and Democrats have focused the last 50 years of higher education policy on: increasing access, increase completion, and more recently lowering costs. The easiest way to increase college access, completion and make it cheaper – is to lower standards. It’s the easiest way. Anyone can go, anyone can finish and it’ll be cheaper.

If you actually educate your citizenry, and not just drive people towards the same credentials, more of the population will be ready to take the next step. When you apply science of learning, students are more engaged and are ready to make informed choices. Completion rates then increase. Thirdly, as education institutions focus on education, then they can shed all of the outrageous cost levels that universities are currently in the trap of doing: sports, research salaries, campus museum and performing arts centers. The cost burden of creating these country clubs falls to students and tax-payers but what’s the ROI? If higher ed actually focused on education, then we could solve this. College access and completion rates are only symptoms. You have to treat the root cause.

Ben’s One Good Question: How do you enable wise decision-making in a world with unwise people? I don’t know the answer to that. I know how to make less and less wise decisions accelerate—social media, balkanization, knowledge migration – all these trends and realities are pushing us in the wrong direction.

Ben Nelson is Founder, Chairman, and CEO of Minerva, and a visionary with a passion to reinvent higher education. Prior to Minerva, Nelson spent more than 10 years at Snapfish, where he helped build the company from startup to the world’s largest personal publishing service. With over 42 million transactions across 22 countries, nearly five times greater than its closest competitor, Snapfish is among the top e-commerce services in the world. Serving as CEO from 2005 through 2010, Nelson began his tenure at Snapfish by leading the company’s sale to Hewlett Packard for $300 million. Prior to joining Snapfish, Nelson was President and CEO of Community Ventures, a network of locally branded portals for American communities.Nelson’s passion for reforming undergraduate education was first sparked at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School, where he received a B.S. in Economics. After creating a blueprint for curricular reform in his first year of school, Nelson went on to become the chair of the Student Committee on Undergraduate Education (SCUE), a pedagogical think tank that is the oldest and only non-elected student government body at the University of Pennsylvania.

One Good Question with Ana Poncé: Is School Enough for Our Kids?

This post is part of a series of interviews with international educators, policy makers, and leaders titled “One Good Question.” These interviews provide answers to my One Good Question and uncover new questions about education’s impact on the future.

“In what ways do our investments in education reveal our beliefs about the next generation’s role in the world?”

Our mission at Camino Nuevo is to prepare students to succeed in life; we want our kids to be compassionate leaders, critical thinkers, and problem solvers and to thrive in a culturally-connected and changing world. But we can’t do this work alone. We need families to be our partners. That’s why, from the beginning, when we opened our first school, one of our priorities was institutionalizing an authentic parent engagement program with a robust menu of support services. We try to get to know families and understand their needs. When a family needs help, our staff connects them with existing support services in our community. Our commitment to families is paying off: Nearly 100 percent of our students graduate and are college bound.

There is a perception that running an effective parent engagement and support services program costs millions of dollars. However, it’s all about the partnerships and how schools integrate the support structures into the day. For example, our schools are able to offer mental health counseling because we partner with a nonprofit mental health provider in the community. We also partner with graduate schools that provide us with interns. Through this partnership model, we can provide services to about 2,000 youth at a fraction of the total cost. We have similar partnerships for our students to have access to the arts, science, mentoring, and afterschool programming. These resources and services are available in many communities.

“Without dedicated funding available, so many schools feel like they have to choose between academic supports and mental health supports. Why not just rely on community agencies to respond to these needs?”

Schools don’t have to provide every direct service. However, it is time that schools embrace collaboration and coordination. As educators, we know when families are struggling because a family member will turn to a teacher or staff member they trust to ask for help. Sometimes we find out [about a need] because a student is acting out due to the stress or trauma imposed by a family’s situation. That’s when we can connect those families with support agencies. We’ve had situations, for example, when a child’s family member has been deported, our staff has connected the student and their family to support services because we know how traumatic this situation can be for everyone. We do the same when we hear of a family who may be at risk of being evicted from their home. Everyone — from school leaders to custodians to office assistants – is trained on the referral process as well as our partnership philosophy. So, if a school’s office manager hears about a family in need, that person knows something can be done about it and knows who can connect the family to the services they need.

“When we grow up in under-served communities and teach/lead in those same communities, we want to provide our students more access than we had. Is that enough? Does today's generation of (insert your demographic here) need something different than we did?”

It gives me pause when I hear people say “Is that enough?” What is enough? What does that mean? Ten years ago I was meeting with a program officer who asked when our work would be “done” in the MacArthur Park community. [laughter]What’s happening here, in terms of the consequences of poverty, is so beyond what we can do as a school. When I think about what is enough, I know that school is not enough. We have a lot more to do and we need a lot more of us to do it. I believe that we need to create culturally reflective environments where our children are seeing themselves, and who they can become, on a daily basis. As People of Color, we come into the education space and some stay for a few years, others stay longer. I don’t think we are doing enough in diversifying the education workforce. I believe we need to do more to prepare people of color for college success so that we can recruit more teachers of color, more leaders of color in education and education adjacent fields.

It’s important that our communities support more of us coming back in some way. It doesn’t mean that you have to come back and live in the same community. You can “come back” in different ways – teach or lead in a school site, work in an education nonprofit. Our kids need to see us come back and inspire them. When they see people who look like them in positions of influence (principals, C-level organizational leaders, key board members) and engaging in different activities (in college fairs, arts programs, ethnic studies classes) – their perception of what is possible for them begins to change.Camino Nuevo students are getting a lot more, in many ways, than I or my peers did back in the day, when high school completion was the exception, not the norm, for kids like me. Is it enough? In some ways it is; more personalized attention, more wrap-around services, more enrichment opportunities, more access to higher education. However, our kids still need more because the system is so broken and set up against their success. Our students need more than a solid educational foundation to make them competitive and to help them navigate the system. Higher education needs to rethink how it supports first-generation college student to completion. We have a solid track record of getting our kids to pursue higher education options and many of them are encountering significant barriers that most often are not academically related. What we are doing at CNCA is great and it is a lot “more,” but I don’t believe that it is enough because of the barriers our kids continue to face every day due to systemic injustice.

Ana’s One Good Question: As a nation, we’re struggling with low college completion rates. We’re seeing a slight increase in graduation rates for Latinos, but a lot of our kids start college and don’t finish. Education leaders and opinion influencers are rethinking the goals of K-12. I’m really concerned that more folks are thinking about creating alternate pathways for Latinos that don’t include a college education. That’s constantly on my mind. I know that my students, my kids will need a college degree to be competitive and to be on the path to leadership and influential positions. I am committed to educating all our kids to be leaders in their communities and in their fields. When we start creating watered-down pathways to a job, we’re not setting our students up to be leaders. What does that say about what we’re really trying to do? I’m personally committed to figuring out how we move 'average students' to attain higher levels of success beyond being at top of class. Jumping to alternative pathways is a quick solution. But let’s think about the consequences and examine what we as educators and what our institutions are not getting right. Let’s not blame the kids just yet. Let’s turn the mirror on ourselves.

Ana Ponce is the Chief Executive Officer of Camino Nuevo Charter Academy (CNCA), a network of high performing charter schools serving more than 3,500 Pre-K through 12th grade students in the greater MacArthur Park neighborhood near Downtown Los Angeles. CNCA schools are recognized as models for serving predominantly Latino English Language Learners and have won various awards and distinctions including the Title 1 Academic Achievement Award, the California Association of Bilingual Education Seal of Excellence, the California Distinguished Schools award, and the Effective Practice Incentive Community (EPIC) award. Born in Mexico, Ana is committed to providing high quality educational options for immigrant families in the neighborhood where she grew up.An alumnus of Teach for America, she spent three years in the classroom before becoming one of the founding teachers and administrators at The Accelerated School, the first independent charter school in South Los Angeles. Under her instructional leadership, The Accelerated School was named “Elementary School of the Year” by Time magazine in 2001. Ms. Ponce earned her undergraduate degree from Middlebury College and a master's degree in Bilingual-Bicultural Education from Teachers College, Columbia University. She earned her administrative Tier 1 credential and second master's degree from UCLA through the Principal's Leadership Institute (PLI) and earned a Doctorate in Educational Leadership from Loyola Marymount University. A veteran of the charter school movement in California, she serves on the Board of the California Charter Schools Association.

One Good Question with Connie K. Chung: How can we Build Systems to Support Powerful Learning?

This post is part of a series of interviews with international educators, policy makers, and leaders titled “One Good Question.” These interviews provide answers to my One Good Question (outlined in About) and uncover new questions about education’s impact on the future.

“In what ways do our investments in education reveal our beliefs about the next generation’s role in the world?”

Different communities are investing in their young people in different kinds of ways. Who is deciding how the investment is made is also an indicator of what we value of the next generation. Young people’s voices and even teachers’ voices can be included on a larger scale. Going forward, given the rapid shifts of what we need to teach our young people, and the current emphasis on personalized learning, those two groups of people are essential to include in deciding that what future investments might be.

A good investment requires a diversified portfolio. We’re going to need a diversified portfolio to figure out what we’re doing for the future. Much of our current investments are in developing cognition. So much of how we have invested our money, energy, time, human resources, attention and discourse, has recently been around testing. I do think testing does help for accountability, transparency, and promoting quality to a certain degree. But it’s not enough. We need more investments in the following:

developing a more holistic vision and purposes for education, that is child-centered

developing systems that are responsive to the needs of the present and the future

strategizing and visioneering to create systems in which parts work together

obtaining consistent, impactful leadership. Average turnover for superintendents in the US is 2.9 years, which isn’t enough to develop sustainable, responsive, or adequate systems for what the students need.

creating adequate space, time, and resources for teachers to learn while they are teaching. The technology and content is changing so rapidly that it requires continual learning, even for teachers.

We need to develop systems to learn from each other. I know lots of great examples of powerful teachers, schools, and networks like United World College (UWC), EL Education, and High Tech High (HTH) doing wonderful work. But I don’t see a lot of investment in ways to systematically identifying, cataloguing, curating, and making transparent and transferable some of these processes for teachers, school leaders, and heads of systems. What might be sustainable models for teachers to continue to learn in their PLCs, schools, district and region?

“What’s keeping us from making that kind of investment in US?”

It would be helpful to enable cultures and conditions where teachers’ voices are heard. I’ve seen this at EL Education schools in the US. Many of their schools have restructured their school time to enable more teachers to collaborate in interdisciplinary teams and let students do projects in longer blocks of time. Some EL Education schools have even restructured the spaces within the schools for the collaboration to occur. So that work is happening, but it’s not happening at a larger scale. In those places like EL Education, they have leadership that is listening to teachers and thinking about how to establish the conditions so that the real learning happens. They’re not so invested in finding the next silver bullet, but in developing whole school cultures that enable continual learning and growth in community to happen.

“In Teaching and Learning for the Twenty-first Century: Educational Goals, Policies, and Curricula from Six Nations, one of your findings is that countries emphasize cognitive domains over interpersonal and intrapersonal domains in their K-12 curriculum. Why does that matter?”

Learning is cognitive, but it’s also social and emotional. For example, we can look at Tony Bryk’s work on trust in schools. The places where student achievement increased were places with a culture of trust. These are environments where people felt able and vulnerable to say “This is what I need to learn and grow,” and felt safe socially and emotionally to do that. And they have communities that supported that vulnerability instead of punishing and hiding it. Carol Dweck’s work is about not just growth mindset for students but could be applied to teachers as well. The process of learning is not just cerebral, but being vulnerable and humble, and takes place in supportive and collaborative school culture that, listens to and learns from, and challenges each other. The more we acknowledge and understand that, and then build our systems to support not just the development of cognition, but cultures, systems, and relationship building, that’s the hard work that needs to be done now. It’s not magic.

I’ve heard too many times about cases where school districts pivoted and adopted a curriculum that’s student centered and adapted to the 21st century but without other support systems and structures to enable that change. But as several educational leaders have noted, “Culture eats policy for breakfast.” Even in China, our colleagues also found that, in their innovative schools districts, their broader district culture embraces innovations and trying new things. We might continue to recognize and cultivate leaders who pay attention to how to build cultures and environments that enable students and teachers to do this kind of work. We need a shift in the kinds of questions that we’re asking, a shift in processes and frameworks, not just in acquiring a new curriculum.In a 19th century factory model, where we you want to get the process right for mass production, quality was defined by consistency. The 21st century model is a sharing economy in which people all have the ability to be creators. The ability to cultivate systems and cultures that enables that to happen, where people feel empowered and equipped, is perhaps just as important as paying attention to individual components like curriculum. I think the cultural piece can’t be emphasized enough – values, attitudes, relationships, and structures. How do we create that kind of environment?

“How do we do this without over-testing social-emotional learning?”

The ultimate assessment is: are we going to survive and thrive as a country? Have we created students through our school systems who are going to live well together and promote their own and others’ well-being? That’s the ultimate high-stakes assessment! We may have people who have tested well in schools but may well be failing this real assessment around whether we can create a sustainable future together.This goes back to the purpose of education, which is important to look at as a guide. We’ve overemphasized assessment to guide us. Assessment is one indicator for achieving our broader purpose, but we’ve disproportionally given power to assessment to drive the entire endeavor of education. It’s a tool, but testing well is just part, not the entire purpose and end goal of education – personal, social, and global well-being are. For example, OECD is driving towards these broader outcomes with their Education 2030 plan; it focuses more on creating positive value and well-being for example. UNESCO is also arguing for education being a critical part of building sustainable futures for everyone on the planet. If that’s the case, let’s figure out how we can build a better world together, using all of our tools, and not solely rely on narrow indicators.

Connie’s One Good Question: Much of what we think is necessary for students to learn is already happening, just only in pockets and for certain students and not for others. That said, I have a lot of questions! How do we rapidly make sure that all students are receiving and engaging in this kind of education? What roles could researchers, policy makers, teachers, parents, and social entrepreneurs all play in this? Are there ways that we can all work together to achieve this for a larger population and wider range of student? How do we collect and connect good people who are already doing this work to make it grow exponentially vs. linearly?

Connie K. Chung is the associate director of the Global Education Innovation Initiative at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, a multi-institution collaborative that works with education institutions in eight countries. She conducts research about civic, global citizenship, and 21st century education. She is especially interested in how to build the capacities of organizations and people to work collaboratively toward providing a relevant, rigorous, meaningful education for all children that not only supports their individual growth but also the growth of their communities. She is the co-editor of the book, Teaching and Learning for the Twenty-First Century: Educational Goals, Policies, and Curricula from Six Nations (2016), a co-author of the curriculum resource, Empowering Global Citizens: A World Course (2016), and a contributor to a book about US education improvement efforts, A Match on Dry Grass: Community Organizing as a Catalyst for School Reform (2011). A former high school English literature teacher, she was nominated by her students for various teaching awards. Connie received her BA, EdM, and EdD from Harvard University and her dissertation analyzed the individual and organizational factors that facilitated people from diverse ethnic, religious, and socio-economic class backgrounds to work together to build a better community.

One Good Question with Susan Patrick: How can we Build Trust in Our Education System?

This is the second interview with Susan Patrick for the series “One Good Question.” These interviews provide answers to my One Good Question and uncover new questions about education’s impact on the future.

“In what ways do our investments in education reveal our beliefs about the next generation’s role in the world?”

There’s a big difference in how you would fund the education system if you were building for the longer term – you would invest in building capacity and trust. We need to take a very honest look at our investments. If people and relationships matter, we need to be building our own sense of inquiry. That’s not at odds with innovation investments. We should be about innovation with equity. That way, we can change our own perspectives while we build new solutions.The debate about top-down reform vs. bottom-up innovation is tied to the same trust issues. In Finland, they made an effort to go towards a trust based model and it meant investing in educator capacity so that the systems trust educators to make the best decisions in real-time. If we don’t start investing in trust, we can’t get anywhere.

“When US educators visit other countries, we tend to look for silver bullet programs from the highest-performing countries. What are we missing in that search?”

During my Eisenhower Fellowship, I was able to meet with teams from OECD and UNESCO that gave me great perspective. UNESCO has just published an Education 2030 outlook presenting their global education development agenda that looks at the whole child. Their goals are broad enough to include developing nations who aren’t yet educating 100% of their population. When we read through the goals and indicators, the US could learn a lot from having our current narrow focus on academics. Our current education structure is not going to lead us to provide a better society. Are we even intending to build a better society for the future? We’re not asking the big questions. We’re asking if students can read and do math on grade level in grades 3-8. In Canada, they ask if a student has yet met or exceeded expectations. If not, what are we doing to get them there? You don’t just keep moving and allow our kids to have gaps.The UNESCO report specifies measures about access to quality education. Is there gender equality? Is there equity? They define equity as:

Equity in education is the means to achieving equality. It intends to provide the best opportunities for all students to achieve their full potential and act to address instances of disadvantage which restrict educational achievement. It involves special treatment/action taken to reverse the historical and social disadvantages that prevent learners from accessing and benefiting from education on equal grounds. Equity measures are not fair per se but are implemented to ensure fairness and equality of outcome. (UNESCO 2015)

Across the global landscape of education systems, there is a diversity of governance from top-down to bottom-up regarding system control, school autonomy and self-regulation and how this impacts processes and policies for quality assurance, evaluation and assessments. It is important to realize the top-down and bottom-up dynamics are often a function of levels of trust combined with transparency for data and doing what is best for all kids. In the US, let’s face it, our policy conversations around equity are driven by a historical trend of a massive achievement gap. Said another way, there is a huge lack of trust from the federal government toward states, from states to districts and even down to schools and classrooms. We ask, “How do we trust that we’re advancing equity in our schools?”

However, when you start to think about what we need to do to advance a world-class education for all students and broaden the definition of student success – you hit a wall in coherent policy that would align to better practices. There’s so much mistrust in the system given our history of providing inequalities across the education system, it is inequitable. In recognizing that our education system isn’t based on trust, therefore, perhaps we need to focus on what our ultimate goals and values for our education systems should be and then backward engineer how we get there, how we hold all parties accountable and how we could actually build trust in a future state. We need to consider future-focused approaches that work to build trust, transparency, greater accountability and build capacity for continuous improvement. We do need to assure comparability in testing to tell us whether we have been providing an equitable education. It’s just right now, this lack of trust is creating a false dichotomy of limited approaches to a future-focused education system. We’re defaulting that the only test that we trust is criterion-referenced standardized tests.We need to take a deep look at the implications that systems of assessments mean for the rest of the system. It seems that we’re only willing to trust education outcomes based on a standardized test, that we commit to locking students into age-based cohorts, and that we focus primarily on the delivery of content. What would be the long-term implications for creating better transparency, more frequent inquiry approaches on what is working best for both adults and children? Are there different ways to evaluate student work and determine whether students are building knowledge, broader skills and competencies they need for future success? Can we consider a range of future goals and backward map alternative approaches? All assessments don’t have to be norm-referenced. This is a familiar conversation with education experts globally. I’m afraid we’re not having that conversation in the US.

That’s what’s so interesting to me about iNACOL’s work. It’s global and focuses on future states for educators and practitioners designing new models using the research on how students learn best. We listen to practitioners working on next generation designs and then ask, is our policy aligned with actually doing what’s best for kids? What if you could set a vision for a profile of high school graduates that would ensure success? What goals would you want for redefining what students need to know and be able to do? And, how would you then approach aligning the systems of policy and practice with what’s right for kids? The new federal Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) law gives states the flexibility to come up with new definitions of students’ success. States can now use multiple measures — and still report data transparently. This is a really important time to engage in deep conversations between states and communities, families, local leaders and educators around what would we do for redefining success — but I’m not seeing yet any states that are having enough foundational conversations on the ultimate goals and vision of education WITH COMMUNITIES. I’m hearing educational leaders say, “All we know how to do is NCLB” . . . and wonder which other indicators a future accountability system might require. They’re uncomfortable thinking about alternatives. It’s a sort of “Stockholm Syndrome” of educational policy limited by the past. ESSA is an opportunity to engage in real dialogue with the communities we serve. Communities have been locked out of the process for years now. Community outreach has become a box that people check, but it’s an ongoing dialogue and should be about building understanding and trust. This is a really rare opportunity in the United States to engage in a broader conversation around student success with local school boards and communities. This would encourage innovation and provide a clear platform driven by communities on the clear goals and outcomes we hope to achieve in our education system for equity and excellence.

Susan’s One Good Question: Who asks the question is as pertinent as which questions they ask. Earlier, I mentioned that investment in the long-term capacity building of our education system would require building our own sense of inquiry. In other more top-down nationalistic approaches to education in countries outside the US, leaders do control the system so they are having strong “values-based” conversations about education in the context of societal goals, too. Because we are a strong federalist approach to education – this isn’t possible or even desired at a national level . . . the US Department of Education doesn’t have a federal role in that way, and quite frankly, we can’t have a national or even state-level values-based conversation in the same way. In a federalist approach, we have 13,600 school boards with local control. The unit of change in this country is the local school district (LEA means local education authority). School leaders, superintendents, CMO leaders -- they actually can drive the values conversation about what our educational goals, vision and values are and how we measure success transparently. We’ve stopped talking about values in the name of objectives related to literacy and numeracy. I believe literacy and numeracy are extremely important, but let’s not forget that foundation for reading and arithmetic (with all students having proficiency) is not enough in the modern world. For students to be successful it is a “yes, and . . . “ with literacy and numeracy being important but not enough. I don’t know how schools can address the extreme inequities in our education without having a values conversation and a re-framing of conversations around re-defining student success with broader definitions of student success.I think that our local communities should start asking themselves these two questions:

When a student graduates what should they know and be able to do?

What is our definition of student success?

Susan Patrick is the President and Chief Executive Officer of the International Association for K-12 Online Learning (iNACOL). iNACOL is a nonprofit providing policy advocacy, publishing research, developing quality standards, and driving the transformation to personalized, competency-based, blended and online learning forward.She is the former Director of the Office of Educational Technology at the U.S. Department of Education and wrote the National Educational Technology Plan in 2005 for Congress. She served as legislative liaison for Governor Hull in Arizona, ran a distance learning campus as a Site Director for Old Dominion University’s TELETECHNET program, and served as legislative staff on Capitol Hill. Patrick was awarded an Eisenhower Fellowship in 2016. In 2014, she was named a Pahara–Aspen Education Fellow. In 2011, she was named to the International Advisory Board for the European Union program for lifelong learning. Patrick holds a master’s degree from the University of Southern California and a bachelor’s degree from Colorado College.

One Good Question with Anna Hall: Can You Break Up with Your Best Ideas?

This post is part of a series of interviews with international educators, policy makers, and leaders titled “One Good Question.” These interviews provide answers to my One Good Question (outlined in About) and uncover new questions about education’s impact on the future.

“In what ways do our investments in education reveal our beliefs about the next generation’s role in the world?”

Our field collectively is investing in new school development and in the engines that can generate new designs for school. Those two things sometimes happen simultaneously, and sometimes run on parallel tracks. In the new school development work, there are districts and cities around the country that have invested very heavily in opening new schools to change the paradigm for what high schools could be — NY, DC, and NOLA come to mind. Deeply embedded in that investment is a commitment to equity and choice - as a system we are committed to creating great opportunities for young people and ensuring that they and their families have a range of choices for where they want to go. That’s urgent, exciting work.But in addition to offering more great high schools, we know that we also need to make sure that we have evolved high schools – with designs that advance as quickly as the world we live in. It’s important to acknowledge that creating a truly world class system of 21st century-ready schools will require a multitude of design solutions – or models. It’s inspiring to be able to work simultaneously in new school design efforts that focus on that challenge.

“Why does equity matter in school design?”

Learning is part of becoming a fully formed, socially- and culturally-engaged human. We all have a right to do it, and our society has a responsibility to create those learning opportunities. All kids should have a chance to go to a great school, designed to support them and give them opportunities to shine. I came to teaching, in fact, because in my 20s I worked for a child welfare agency whose stated chief academic goal for the young people in its care was that they achieve their GED. I was deeply disturbed by the inequity and unfairness of that premise – by the idea that our system would organize around such low expectations for young people who had already navigated so much trauma and struggle in their lives. I knew kids could do more, given the right opportunity and support. I joined the NYC Teaching Fellows, and have been an educator and a school designer ever since, because I believe we can and must create better systems, better schools, better choices and supports for young people and their families.

“When working with educators on school redesign, how do you narrate the new design process for them?”

It depends. If you’re working with a team attempting to open a new school but not a new model, that’s an easier soup to dive into because things seem known. You’re taking the core of someone else’s practice and building a design around it. We recently published a collection of some of the questions and experiences from the design process that our partners have found most relevant and helpful – but to sum up here, we’ve found that the real challenge for completely new model design is actually reframing the task at hand – understanding that you are trying to create a custom-built school that maps to and builds upon your specific students’ ambitions, dreams, strengths, and needs, not just curating a set of great ideas that could be engaging to any group of kids. And we recognize that “design” is work that school leaders and their teams may engage as part of the process of creating a new concept for a school – but that it continues in perpetuity after the school opens, as part of a robust iteration cycle.

“Stop for a second. Look at the young people in your schools. Consider what path those young people need to get to where they want to go. Then build.”

Step 1: Breaking up If you accept the premise that schools should be built uniquely to serve the students in them, then new school model design requires designers to begin the work without a preconception of what their school will be. In this context, designers don’t have to be married to a certain schedule, or course sequence, or bells, lunch, etc. Instead, we encourage them to launch their design work by developing a deep understanding of the students and families their school will serve, and build from there. This “frame-breaking” work can be challenging, but it can also be really creative and fun. It lets us think about how to organize school around what our kids need.

Step 2: Wow! We have inspired the most beautiful design! Often, design teams come up with inspiring, innovative design concepts that look great on paper. But the act of translating the design into systems that work for faculty and all of the families and young people is often when folks hit the second wall. Again, we encourage design teams to look at their designs through the lens of student needs and assets, and prioritize based on local context and realities.

Step 3: Oh Crap! This is often how teams react when they have to decide how to actually bring their designs to life. They have to answer many questions: In which order will we create and roll out each design element? Which people do we try to hire and recruit who will be willing to do this? What is the enrollment pattern around our school and its ecosystem? How do we both navigate logistics and protect our model? It’s an intellectual puzzle—arranging the pieces and putting everything in place. It can be a messy exercise.

Step 4: Euphoria When schools open for the first time, and through the first few weeks, team often feel like they’re walking on air: “We made a thing! A real thing! People are here! Children are here! They’re doing things that look like school. It’s amazing!!!!!” It is really a lovely moment, while it lasts.

Step 5: Breaking up (again) Shortly thereafter, things start to break or not work. The ideas that were awesome might not fit because a team couldn’t predict what their students would need or want or respond well to, or what might not work in practice. We help our partners navigate that first wave of struggle: my original ideas were not perfect, so what’s the path forward? How do you break up with the parts of your idea that just don’t fit your current reality? How do you deal with that emotionally? Then, practically speaking, because you have young people in the space and adults who are trying to do their job well— how do you make shifts strategically, without causing too much disruption and stress? Consistency is important - how do you maintain a baseline of quality for your kids that you can sustain, whatever your changes?

“I love that students are your starting and ending point! How much do students participate in this process?”

Our position is that we want students to participate fully and as much as possible in the process. When we started this work, our first school partners already knew which communities their new schools would serve and where their feeder schools were. This was a great opportunity, which meant teams wouldn’t have to design in abstract – they could solve for specific challenges. So as we developed our process, we saw that student knowledge as an asset and designed a process that capitalizes on that information.

Given that, as I mentioned before, we believe that every school design team needs to start with a deep immersion in the process of understanding the community and families and students that the new school will serve. Instead of starting with an academic model, we encourage designers to spend time talking to families and kids. What are their ambitions, dreams, hopes, skills & knowledge? What do they hope the school will be? We pair that process with qualitative and quantitative data exploration. Brainstorming sessions with families and kids from the feeder schools can also be valuable. Some schools go beyond and have students as full members of the design team and/or the launch team. That involvement varies depending on each school’s constraints.

Anna’s One Good Question: The thing I’m always trying to figure out when looking at new school design is: Does this new design create opportunities for kids or does this design prove/support an idea?We’ve got to continuously ask this of ourselves when designing schools. And we’ve got to be careful not to be too rigid in school design. It’s pretty straightforward to read a book about a strong school model, or to visit and observe one – and then to distill the model’s concept or “rules”, and commit to executing the idea with precision and perfection. But that approach can be limiting. We need to always be willing to analyze which parts of any given school model will work for our kids, which don’t, and which we need to change.

Anna Hall is Senior Director of Springpoint: Partners in School Design. Anna is a seasoned educator with experience developing and leading a range of institutional, state, and national initiatives. As a founding teacher of a highly successful small New York City public high school, she collaborated to design and build an innovative and rigorous secondary program for students in the South Bronx – and then, as principal, she led the school’s expansion and redesigned its academic programs. Prior to teaching, Anna spent nearly a decade working as a writer, researcher, and project manager in a range of policy, politics, and technology firms.Anna holds a B.A. from the South Carolina Honors College at the University of South Carolina, and an M.S. in teaching from Fordham University. She is a graduate of both the New York City Teaching Fellows Program and the New York City Leadership Academy.Download a copy of Springpoint’s School Design Guide here.

One Good Question with Nicole Young: Can Students and Teachers Impact Ed Policy?

This post is part of a series of interviews with international educators, policy makers, and leaders titled “One Good Question.” These interviews provide answers to my One Good Question and uncover new questions about education’s impact on the future.

“In what ways do our investments in education reveal our beliefs about the next generation’s role in the world?”

Particularly for children of color and low income students, we are not creating students who can invent a new system, but students who can perform well in the current system. And we know that the current system is flawed. We need to be creating youth who can create a new system, and disrupt this one.Beyond the structural school redesign needs, I actually question how we include students’ voice in the creation of that new system. What would the outcome be if we had student voices at the table and not elective to the conversation but essential to the conversation ? What if we didn’t know anything about how the policies were made and we could just invent the systems that our kids need?

“How does that level of engagement start?”

It starts on individual schools and campuses. We’re thinking about it more on our campus, but we’re not great at it yet. We have an advanced seminar this year and the students brainstormed what they want to do to complete their capstone assignment. Instructors took their ideas and synthesize them into 8 great options that students could choose from. We have to think about how to make those not moments of isolation, but the norm.

Other questions that we’re asking ourselves: How do we have student/alumni voice on our Board? How do we have students direct change? As our students are starting to organize, we wonder if their role is to create a glorified social club or to help us drive changes on campus. These strategies are not just for my 11th and 12th graders. Elementary students have voice that can influence their learning space. So many adults are thinking about hallway transitions and how to avoid 20 kindergarteners piled up on each other every time they leave the room. Could kindergartners think through that ? I think so! And as a result, their investment in that solution could work. It starts at the school level and then upwards to state policy.

“What keeps us from shifting student voice from being a “nice to have” to an essential element?”

Socialization. We were raised that the younger you are, the less important your voice is. The same way that you have to break down biases in other realms, we have to put as much emphasis around the limitations of age. It’s important to recognize the science that, yes, youth brains are not developed in the same way as adults, but different doesn’t mean deficient.

“Are we talking about youth-led change or youth-informed change?”

In practice we start with youth-informed and then move towards youth-led. I don’t know that we could get to a state or federal policy that was youth-led. But I think if you had a really progressive group of people, on a campus or in a district—you could get true youth leadership there. Start by giving students real problems to solve, asking for their ideas/needs and then draft a few models that might respond. Bring your drafts back to the youth council to test it with them.

“What do education policy makers need to know about school leadership?”

We’ve had backlash around sweeping federal education policies, but I think it’s less about the content and more about the idea generation process. With No Child Left Behind (NCLB), teachers didn’t feel that it was informed by real-life experiences in the classroom. I wonder if educators would have felt differently about NCLB if the process included youth and current teacher practitioners? Even a little bit of distance from teaching and school administration means that you’ve lost some memory of that experience.

Policy makers occasionally visit schools and feel like that glimpse is enough to inform their decisions. Everyone knows that when the Feds come to visit your classroom, it is going to be the best day. Even students know it! I would encourage policy makers to spend more time on listening tours and hosting idea generation sessions with teachers and administration.Teachers and school leaders have to feel like their ideas can move from idea generation to real policy. Great ideas about what works on the ground may not translate directly to a policy. The gap is that policy makers think that, just because a teacher isn’t talking policy, they don’t have anything to contribute. At the same time, teachers feel like since they don’t speak the policy language, they are disempowered to offer their ideas.

“It’s almost like some parent-teacher dynamics.”

Yes! Parents know their children, but don’t have the language around pedagogy to advocate for specific changes. Practitioners need more thinking about how to translate their ideas into policy.

Nicole’s One Good Question: If you ask parents what success looks like for their kids, they may say “a happy, healthy life where they are secure.” Many may place happiness at the center. When those same parents talk about other people’s children, the success gets murkier. If we’re focused on all children, then we should be able to back map their needs. What role does education play in realizing the parent’s dream of success and happiness for every child?

Nicole Young is Executive Director of Bard Early College, New Orleans (BECNO). Young graduated from the University of South Carolina in 2007 and immediately began work on the Obama Presidential Campaign. After 2008, she lived in Washington, DC for four years working at the U.S. Department of Education and the White House Office of Presidential Personnel. Before coming to BECNO, Young served as the Associate Director for Social Justice at the College Board where she worked to evaluate, support, and expand the College Board’s work for students of color. Young received her Master’s Degree in Education Policy at The University of Pennsylvania.

One Good Question with Aylon Samouha: Is There a Silver Bullet for the Future of "School"?

Aylon Samouha

This post is part of a series of interviews with international educators, policy makers, and leaders titled “One Good Question.” These interviews provide answers to my One Good Question (outlined in About) and uncover new questions about education’s impact on the future.

“In what ways do our investments in education reveal our beliefs about the next generation’s role in the world?”

Thankfully, there is a lot of investment in education, both public and philanthropic dollars. The sheer quantity of investment is a clear signal – we believe that our generation plays a critical role in the future world and deserves deep investment. That siad, where does it go? There are lots of human capital investments that funders are making in all sorts of ways to attract, evaluate, and train educators. These investments are animated by a critical need in creating great learning environments ; namely, kids need caring adults around them who are effective at teaching, coaching, motivating, etc.On the other hand, human capital funding by itself may unintentionally reinforce the idea that the only or best way for kids to learn is through teacher-centric models where students have little agency over their own learning. With School in the Cloud, Sugata Mitra challenges the role of educators in the learning process. Basically, he was a web developer who said « What would happen if I just put a computer in the wall here? In a low-income neighborhood in India. Kids started using it and they had never touched a computer before. They looked up stuff and started learning things. Then he said, let me do it somewhere where there aren’t a bunch of techies around. And this time he gave the users a question to figure out. When he asked for their feedback, they said We have to learn English in order to use it. And they actually did learn English to figure out how to keep accessing the tool!

This is an extreme but very instructive example that, with the right tools and motivations, students will self-direct their own learning. So we have to ask ourselves, is it enough to invest in human capital when the underlying traditional model, by its design, under-leverages the innate motivation of students to self-direct their learning ? And what might that say about how we conceive of their place in the world ?Another important and laudable category of investments go towards scaling good schools. This comes from a very good place and should continue – if we’re seeing a good learning environment in one place we should try to replicate that in more communities especially where educational opportunities are poor. That said, an unintended consequences of scale investments is that half-baked things grow before they’re really proven and successful operators sometimes grow faster than the quality can keep up.

Scaling education models is an efficiency play and lots of students and families have had significantly better education choices and experiences as a result of these investments. Counting and expanding quality seats is critical work. That said, what unintended narratives might animate these investments? To what extent are we saying that we need quality seats so that our students can be competitive in the global marketplace? Instead, how might we expand quality seats while reinforcing a narrative that an American student from New Orleans should be working with her brothers and sisters in China to make the world a better place and not merely trying to outcompete them? And when we scale into new communities quickly, to what extent are we going fast alone vs. going further together? This is all a tricky balancing act and I’m heartened to see so many in this work asking these questions more often and more publicly.

“Education leaders around the world are asking themselves « What’s next ? » Our industrial model of education is no longer preparing youth for today’s careers or knowledge economy. Is there a single answer, silver bullet that will emerge in the next iteration of school?”

I definitely don’t think there is a silver bullet in terms of one type of school or kind of pedagogy. But there are some very provocative ideas and shifts that I think will help us massively improve learning across the world. Right now, I’m enthralled by Todd Rose’s work and The End of Average. I won’t do his work justice but a core premise is that « any system that is trying to fit the individual is actually doomed to fail. Waking up from what he calls the « myth of average » seems critical to redesigning the traditional model which essentially holds the average student as a foundational principle. And just like there is no average student there are likewise no average communities. Taken together, we need to build models that respect and leverage the uniqueness of each student ; and, we need to scale those models and ideas in ways that communities can adopt and adapt into to fit their unique values, assets, etc. Generic, cookie-cutter replication may work for enterprises where people have very basic expectations and where the stakes are low (i.e., Starbucks, Target). We don’t want schools or learning experiences to be like that. Communities creating and adapting school models for their context – school models that provide students to adapt and create learning for themselves…maybe that’s a silver bullet?

Relatedly, I’m getting more and more excited about the potential of truly leveraging learning science to advance the way that we construct learning experiences. Research on learning and motivation point to new insights every year -- and we need to systematically use these insights in real daily learning environments! To do this right now, educators – who are already stretched in terms of capacity – would need to wade through endless research papers, discern the usable knowledge and then figure out how to apply that knowledge with students. What would it mean for us to systematically create the bridge between research and application? What if people designing learning experiences could benefit from and contribute to an ever-growing learning agenda for the field ? What if more learning engineers were building and iterating school model components based in the science that educators could readily adapt into their communities? Ok, maybe that’s another silver bullet after-all!

Aylon’s One Good Question: How can we ensure that schools are wildly motivating for all students?

Aylon Samouha is Co-Founder of Transcend Education, a national non-profit committed to building the future’s schools today. Transcend works with school operators across the district, charter, and independent school sectors. They provide and develop world-class R&D capacity that supports visionary education leaders to build and replicate breakthrough learning environments. The co-founders and founding board members published Dissatisfied, Yet Optimistic to put forward their theory of change.Prior to co-founding Transcend, Aylon was an independent designer providing strategy and design services to education organizations, schools, and foundations. Most recently, Aylon has been leading the “Greenfield” school model design for the Achievement First Network, which is being piloted in the 2015-16 school year. He also led the field research for Charter School Growth Fund and the Clay Christensen Institute for the 2014 publication, "Schools and Software: What's Now, What's Next". In 2013, Aylon pioneered the Chicago Breakthrough Schools Fellowship in conjunction with New Schools for Chicago, NGLC, and the Broad Foundation.

One Good Question with Nicole de Beaufort: What if We Built Ed Funding on Abundance, Not Scarcity?

This post is part of a series of interviews with international educators, policy makers, and leaders titled “One Good Question.” These interviews provide answers to my One Good Question and uncover new questions about education’s impact on the future.

“In what ways do our investments in education reveal our beliefs about the next generation’s role in the world?”

I try to look at this question through multiple lenses, those of foundations, government, and direct services side, as well as that of the ultimate end user -- families. Ultimately, I want to know how well people are informing stakeholders about problems and solutions. In Detroit, much of my work is in early childhood. One of the questions I hear a lot from practitioners is Why are we always just at minimum? Why is funding minimum? What would happen if we built formulas for the abundance, not the scarcity? We’re always working on minimums of state and federal funding and that has a negative effect on the system.When we mold to the minimum, we’re building for somebody else’s kids. It’s discrimination against poor people. When an early education professional with two master’s degrees makes $10-12 /hour, the system is broken. When every month or quarter early childhood centers have to justify their existence and they have already stretched every dollar, the system is broken. We have normalized these low investments and expect people to make miracles happen for the next generation without sufficient capacity.

What would change things?

Universal Pre-K that’s not defined by your zip code. No matter who you are or where you live, you should get the same education.

Pay equity. Early childhood educators are barely paid more than fast food workers. We can’t deliver high-quality universal pre-K until we start respecting our educators.

Remove institutional barriers to early childhood access. Models like half-day pre-K are false choices for low-income families. In places like Detroit, where there’s not much transit or cars, there are structural barriers to such models. It takes 90 minutes to drop your kids off, then if you’re a few minutes late, your child is turned away, and you have to take them home on the same 90-minute bus ride. At some point parents decide that it’s not worth the trouble.

Make parent involvement about partnership, not compliance. The lack of transit infrastructure is compounded by punitive compliance-driven practices at the school level. Successful universal pre-K will have parent engagement goals that are relevant and focused on developmental supports for their children.

“Earlier in our conversation you said that it takes at least 10 years for structural change to happen. What do the next 10 years of this work look like in Michigan?”

In the beginning, focus on state and local partnerships. Engage in common visioning and develop common understanding of the realities of local, state, and federal funding streams. This Citizen’s Research Council catalog is a good start. Data creates space for decision-makers to identify our strengths, our capacity, and our inadequacies. For example, a recent IFF study shows the gap between the available quality seats in early childhood education and the kids in need. The highest need goes in a band around the city and into the suburbs. If we were all reviewing that information, we would see that this is not a Detroit problem, it’s a regional problem.Once there’s a shared understanding of where to go (vision) and why (purpose), tackle the question: How do you turn a regional issue into a workable issue? For example, with their Science and Cultural Facilities District, Denver created a tax which enabled some regional thinking about the solutions. A proposal like that could be helpful for building a regional conversation on early childhood. At present, Dearborn and Detroit don’t think that they have the same problems.Finally, focus on impact metrics: How will we know that universal early childhood is working? When we see parent demand for quality early childhood rise. When quality early childhood programs don’t have empty seats. When you have robust public conversation about quality of life for parents with young kids. When the conversation is actively about learning, no longer bemoaning the fact that we don’t have good options. Once the focus is more on the nuance of what/how our children are learning and less on how the institution is performing, we’ll know that we’ve achieved universal access of acceptable quality for all families.

Nicole’s One Good Question: The Flint water crisis is fueling many questions for me, and while we don’t hear about it every day, I wonder about its long term impacts on society. How do we create cities and communities where we don’t have decisions made solely on economic terms? How do we address the divide between the Dollar Store community and the Amazon community? People are our biggest educators. How we live and how we organize our communities is a key part of our education too.“We have too many Americas where people are never seeing each other”.

Nicole de Beaufort is a social entrepreneur based in Detroit, Michigan. She leads EarlyWorks, llc., a strategic communications and community engagement consultancy focused on building awareness and public support for children’s issues.She is also co-founder of Cadre Studio, a service design collaborative using human-centered design methods withphilanthropists to increase impact and effectiveness. De Beaufort co-founded the Detroit Women’s Leadership Network, a mentoringnetwork of more than 1800 women in the Detroit region that was formedpromote inclusive and diverse women’s leadership. Prior to this, deBeaufort served as vice president of Excellent Schools Detroit, an education coalition. She previously founded and led Fourth Sector Consulting, Inc., and served as communications director of the W.K. Kellogg Foundation. Find her at @NicoledeB and earlyworksllc.com

One Good Question with Fabrice Jaumont: How Parent Organizing Leads to Revolution.

This post is part of a series of interviews with international educators, policy makers, and leaders titled “One Good Question.” These interviews provide answers to my One Good Question and uncover new questions about education’s impact on the future.

“In what ways do our investments in education reveal our beliefs about the next generation’s role in the world?”

Part of my research, and the recent book that I have published[1], focus on philanthropy and American foundations, particularly those that make financial investments in education development in Africa. I also work with philanthropists on a regular basis through my work in bilingual education in the United States. I raise funds for my programs which provide services to schools and support the needs of dual language students in various settings. Coming from France, which has a tradition of state-controlled support to education, I have always been intrigued by the U.S. philanthropic culture and tradition of “giving back to the community”, which encourages people, wealthy or not, to contribute financially or by volunteering their time and expertise. This, I find, can have a tremendous impact on children, schools, and communities. I believe it creates better chances for the next generation and help it access quality programs, equal opportunities, and the right conditions to grow and play an active role in society. I find it inspiring to see people giving money willingly – on top of the taxes they pay - to improve a city’s or the country’s education system. The fact that these individuals want to make a difference through their actions and financial contributions is a social contract that I find worthy of our attention. If done well, with the buy-in of communities, it can have an impact on hundreds of thousands of children that would not necessarily have these chances - even within the context of a strong centralized system. This tradition of giving also sends a very strong and hopeful message which is carried on from one generation to the next. As a child, you might have received support from the generosity of someone, perhaps even someone who you never met. As an adult, you might want to be that generous donor and help a child experience things that he or she couldn’t experience otherwise.

We can criticize this tradition too. In recent weeks, a lot has been said about the Gates Foundation’s failure to improve education despite its best intentions, ambitious programs, and the billions of dollars that it poured into transforming schools and educational models. One could ask why, in the first place, foundations and wealthy individuals try to change school systems. Should we not tax these individuals more so that wealth be redistributed through a more democratic process rather than an individual’s pet projects? Surely, the future of our children should not depend on the largesse of the Super Rich.

Sometimes foundations are seen as having a corrosive impact on society. In my book, I analyze these critics’ views of U.S. foundations in Africa. I also provide a new understanding of educational philanthropy by using an institutional lens that helps me avoid the traps and bias that I pinpointed in the discourse of foundation opponents. In my opinion, grantors and grantees have an unequal relationship from the start. As a result, the development agenda is either imposed by the money holders, or “adjusted to please the donor” by money seekers who just want to secure the funds or win the grant competition. To reconcile this discrepancy, I propose that philanthropists and grant recipients place their relationship on an equal footing, and engage in thorough conversations which start with the needs and seeks input from all actors. This can generate more respect and mutual understanding, and strengthen each step of the grantmaking process: from building a jointly-agreed agenda to tackling the issues more efficiently.