One Good Question

Blog Archives

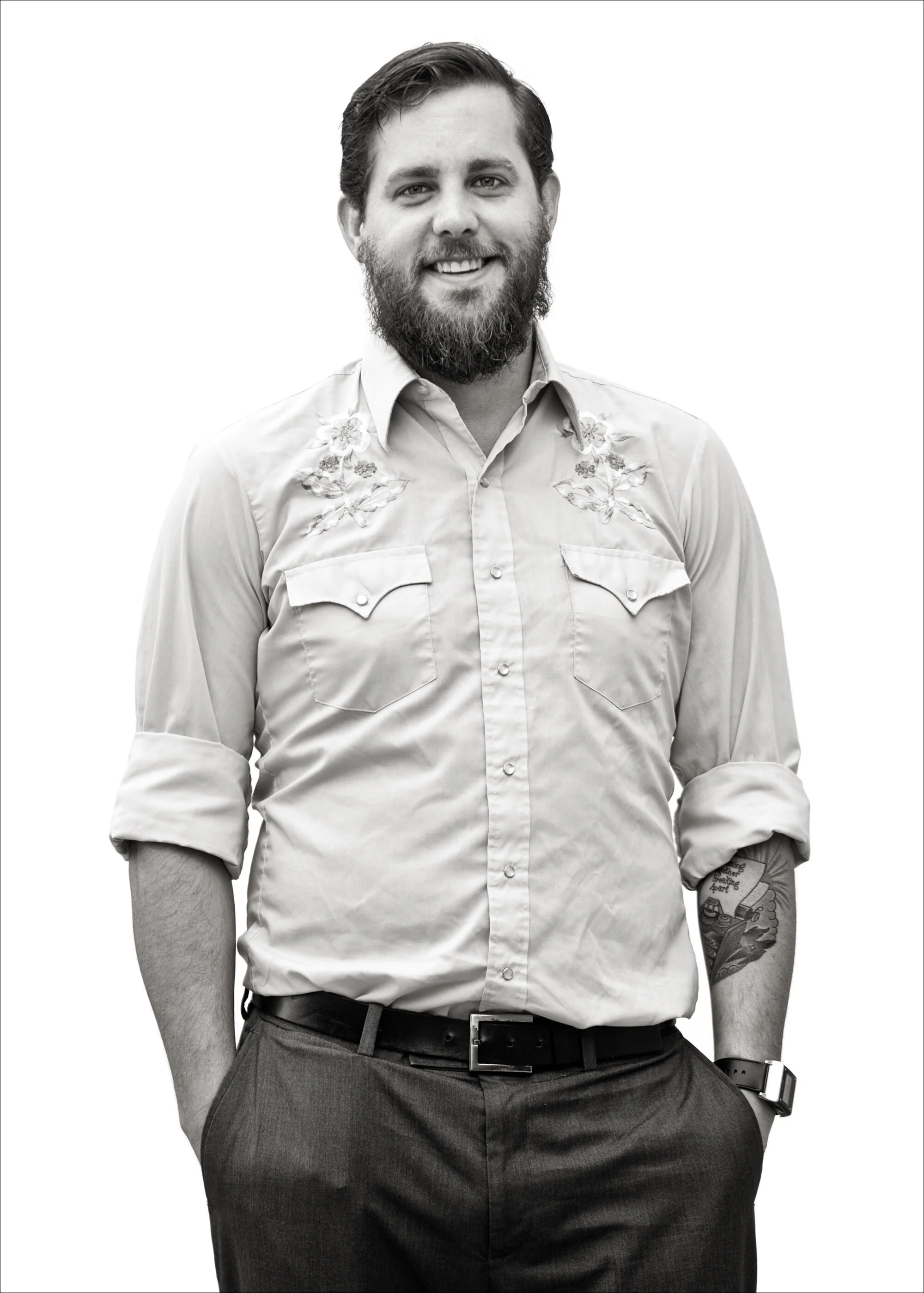

One Good Question with Ben Nelson: Do We Actually Believe that College Matters?

This post is part of a series of interviews with international educators, policy makers, and leaders titled “One Good Question.” These interviews provide answers to my One Good Question (outlined in About) and uncover new questions about education’s impact on the future.

“In what ways do our investments in education reveal our beliefs about the next generation’s role in the world?”

Education matters. It sounds so banal and simple. Everyone in the world says this, but I argue that no one actually believes that education matters. Here’s the proof:Imagine a high school student that has the option to go to A) Harvard or B) some other less prestigious educational institution where they will get a better education. How many people are going to say don’t go to Harvard? Effectively nobody.If people actually believed that education mattered, then college rankings, curricula, and choice wouldn’t exist in these formats. Fundamentally, no one believes that the education matters, but that the credentials matter. People think “have credential, will travel”. And they’re wrong. Credentials actually don’t really matter. Credentials ultimately are put to the test when you get to the real world. The investment – whether dollars, human capital, time and money—from government, private sector, or families—the investment that returns the most in your life is learning. It’s not getting an education.

“You’re shifting the whole paradigm here – learning matters but learning institutions less so? I still believe in "school," so help me understand this.”

We need to make a distinction between getting an education, being educated and actually learning. One of the key elements to know that learning has occurred is the concept called far transfer. Far transfer occurs when people apply learning from one context to a problem/need in a radically different context. You know that some has learned when they say, “I’ve never seen this before, but I’ve seen all of these common elements. I studied XYZ and there are patterns developed between them that I recognize here. With certainty, I know that if I do ABC I will likely get positive results.So for families wondering where to invest in their children’s success? Invest in education, not the credential.

“How do you get people to shift their values towards “education” not credential?”

Hyperbolic discounting is the phenomenon that things get better with age. Among youth and adults—if you are told “you can invest $10 today and get $100 5 years from now” most people say they would rather spend the $10 today. Similarly, when you tell an 18-year old kid, you shouldn’t drop acid/do coke, because you’re going to have a lot of fun tonight, but 10 years from now you may ruin your life. They discount it. This is so built in to human nature to think about short-term reward vs long-term benefit.

It’s hard to admit that you don’t believe in our education system. When push comes to shove and you’re at the supermarket, run into your old friend and she asks where your kid is going to school, you want to say Harvard (or whichever university has status for you). You don’t want to say she’s getting an amazing education at "unbranded institution." You sacrifice the future well-being of your child to have an easier supermarket conversation. That’s how human beings behave.

How do we have a republic that works? People understand and are informed instead of responding to their cognitive biases. They actually commit to spending the time thinking about how not to generate irrational biases. That requires long-term thinking, i.e. I’m going to spend more time pouring through this article, so that my one vote will be a beacon of light and influence others. We’re not built to think that way, even though we live in a world that requires us too. That’s the problem we’re stuck in. We’re not designed for the modern world. We’re still designed to be hunters and gatherers. The only solution I see to our problem is long-term and systemic. Minerva exists to reform education systems all over the world. We believe that reform occurs when the most prestigious institutions reset. Ripple effect goes through the rest of the system. This is a process that will take longer than my lifetime.

Don’t divorce the election outcomes from what government policy has been over the past several decades. Republicans and Democrats have focused the last 50 years of higher education policy on: increasing access, increase completion, and more recently lowering costs. The easiest way to increase college access, completion and make it cheaper – is to lower standards. It’s the easiest way. Anyone can go, anyone can finish and it’ll be cheaper.

If you actually educate your citizenry, and not just drive people towards the same credentials, more of the population will be ready to take the next step. When you apply science of learning, students are more engaged and are ready to make informed choices. Completion rates then increase. Thirdly, as education institutions focus on education, then they can shed all of the outrageous cost levels that universities are currently in the trap of doing: sports, research salaries, campus museum and performing arts centers. The cost burden of creating these country clubs falls to students and tax-payers but what’s the ROI? If higher ed actually focused on education, then we could solve this. College access and completion rates are only symptoms. You have to treat the root cause.

Ben’s One Good Question: How do you enable wise decision-making in a world with unwise people? I don’t know the answer to that. I know how to make less and less wise decisions accelerate—social media, balkanization, knowledge migration – all these trends and realities are pushing us in the wrong direction.

Ben Nelson is Founder, Chairman, and CEO of Minerva, and a visionary with a passion to reinvent higher education. Prior to Minerva, Nelson spent more than 10 years at Snapfish, where he helped build the company from startup to the world’s largest personal publishing service. With over 42 million transactions across 22 countries, nearly five times greater than its closest competitor, Snapfish is among the top e-commerce services in the world. Serving as CEO from 2005 through 2010, Nelson began his tenure at Snapfish by leading the company’s sale to Hewlett Packard for $300 million. Prior to joining Snapfish, Nelson was President and CEO of Community Ventures, a network of locally branded portals for American communities.Nelson’s passion for reforming undergraduate education was first sparked at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School, where he received a B.S. in Economics. After creating a blueprint for curricular reform in his first year of school, Nelson went on to become the chair of the Student Committee on Undergraduate Education (SCUE), a pedagogical think tank that is the oldest and only non-elected student government body at the University of Pennsylvania.

One Good Question with Ana Poncé: Is School Enough for Our Kids?

This post is part of a series of interviews with international educators, policy makers, and leaders titled “One Good Question.” These interviews provide answers to my One Good Question and uncover new questions about education’s impact on the future.

“In what ways do our investments in education reveal our beliefs about the next generation’s role in the world?”

Our mission at Camino Nuevo is to prepare students to succeed in life; we want our kids to be compassionate leaders, critical thinkers, and problem solvers and to thrive in a culturally-connected and changing world. But we can’t do this work alone. We need families to be our partners. That’s why, from the beginning, when we opened our first school, one of our priorities was institutionalizing an authentic parent engagement program with a robust menu of support services. We try to get to know families and understand their needs. When a family needs help, our staff connects them with existing support services in our community. Our commitment to families is paying off: Nearly 100 percent of our students graduate and are college bound.

There is a perception that running an effective parent engagement and support services program costs millions of dollars. However, it’s all about the partnerships and how schools integrate the support structures into the day. For example, our schools are able to offer mental health counseling because we partner with a nonprofit mental health provider in the community. We also partner with graduate schools that provide us with interns. Through this partnership model, we can provide services to about 2,000 youth at a fraction of the total cost. We have similar partnerships for our students to have access to the arts, science, mentoring, and afterschool programming. These resources and services are available in many communities.

“Without dedicated funding available, so many schools feel like they have to choose between academic supports and mental health supports. Why not just rely on community agencies to respond to these needs?”

Schools don’t have to provide every direct service. However, it is time that schools embrace collaboration and coordination. As educators, we know when families are struggling because a family member will turn to a teacher or staff member they trust to ask for help. Sometimes we find out [about a need] because a student is acting out due to the stress or trauma imposed by a family’s situation. That’s when we can connect those families with support agencies. We’ve had situations, for example, when a child’s family member has been deported, our staff has connected the student and their family to support services because we know how traumatic this situation can be for everyone. We do the same when we hear of a family who may be at risk of being evicted from their home. Everyone — from school leaders to custodians to office assistants – is trained on the referral process as well as our partnership philosophy. So, if a school’s office manager hears about a family in need, that person knows something can be done about it and knows who can connect the family to the services they need.

“When we grow up in under-served communities and teach/lead in those same communities, we want to provide our students more access than we had. Is that enough? Does today's generation of (insert your demographic here) need something different than we did?”

It gives me pause when I hear people say “Is that enough?” What is enough? What does that mean? Ten years ago I was meeting with a program officer who asked when our work would be “done” in the MacArthur Park community. [laughter]What’s happening here, in terms of the consequences of poverty, is so beyond what we can do as a school. When I think about what is enough, I know that school is not enough. We have a lot more to do and we need a lot more of us to do it. I believe that we need to create culturally reflective environments where our children are seeing themselves, and who they can become, on a daily basis. As People of Color, we come into the education space and some stay for a few years, others stay longer. I don’t think we are doing enough in diversifying the education workforce. I believe we need to do more to prepare people of color for college success so that we can recruit more teachers of color, more leaders of color in education and education adjacent fields.

It’s important that our communities support more of us coming back in some way. It doesn’t mean that you have to come back and live in the same community. You can “come back” in different ways – teach or lead in a school site, work in an education nonprofit. Our kids need to see us come back and inspire them. When they see people who look like them in positions of influence (principals, C-level organizational leaders, key board members) and engaging in different activities (in college fairs, arts programs, ethnic studies classes) – their perception of what is possible for them begins to change.Camino Nuevo students are getting a lot more, in many ways, than I or my peers did back in the day, when high school completion was the exception, not the norm, for kids like me. Is it enough? In some ways it is; more personalized attention, more wrap-around services, more enrichment opportunities, more access to higher education. However, our kids still need more because the system is so broken and set up against their success. Our students need more than a solid educational foundation to make them competitive and to help them navigate the system. Higher education needs to rethink how it supports first-generation college student to completion. We have a solid track record of getting our kids to pursue higher education options and many of them are encountering significant barriers that most often are not academically related. What we are doing at CNCA is great and it is a lot “more,” but I don’t believe that it is enough because of the barriers our kids continue to face every day due to systemic injustice.

Ana’s One Good Question: As a nation, we’re struggling with low college completion rates. We’re seeing a slight increase in graduation rates for Latinos, but a lot of our kids start college and don’t finish. Education leaders and opinion influencers are rethinking the goals of K-12. I’m really concerned that more folks are thinking about creating alternate pathways for Latinos that don’t include a college education. That’s constantly on my mind. I know that my students, my kids will need a college degree to be competitive and to be on the path to leadership and influential positions. I am committed to educating all our kids to be leaders in their communities and in their fields. When we start creating watered-down pathways to a job, we’re not setting our students up to be leaders. What does that say about what we’re really trying to do? I’m personally committed to figuring out how we move 'average students' to attain higher levels of success beyond being at top of class. Jumping to alternative pathways is a quick solution. But let’s think about the consequences and examine what we as educators and what our institutions are not getting right. Let’s not blame the kids just yet. Let’s turn the mirror on ourselves.

Ana Ponce is the Chief Executive Officer of Camino Nuevo Charter Academy (CNCA), a network of high performing charter schools serving more than 3,500 Pre-K through 12th grade students in the greater MacArthur Park neighborhood near Downtown Los Angeles. CNCA schools are recognized as models for serving predominantly Latino English Language Learners and have won various awards and distinctions including the Title 1 Academic Achievement Award, the California Association of Bilingual Education Seal of Excellence, the California Distinguished Schools award, and the Effective Practice Incentive Community (EPIC) award. Born in Mexico, Ana is committed to providing high quality educational options for immigrant families in the neighborhood where she grew up.An alumnus of Teach for America, she spent three years in the classroom before becoming one of the founding teachers and administrators at The Accelerated School, the first independent charter school in South Los Angeles. Under her instructional leadership, The Accelerated School was named “Elementary School of the Year” by Time magazine in 2001. Ms. Ponce earned her undergraduate degree from Middlebury College and a master's degree in Bilingual-Bicultural Education from Teachers College, Columbia University. She earned her administrative Tier 1 credential and second master's degree from UCLA through the Principal's Leadership Institute (PLI) and earned a Doctorate in Educational Leadership from Loyola Marymount University. A veteran of the charter school movement in California, she serves on the Board of the California Charter Schools Association.

One Good Question with Mike DeGraff: Are Schools Destroying the Maker Movement?

This post is part of a series of interviews with international educators, policy makers, and leaders titled “One Good Question.” These interviews provide answers to my One Good Question and uncover new questions about education’s impact on the future.

“In what ways do our investments in education reveal our beliefs about the next generation’s role in the world?”’

There was a call for 100,000 STEM teachers in the US, and since then there have been tons of initiatives, and related funding, to respond to the need (some say too much). UTEACH is a very constructivist-oriented teacher education program for STEM teachers, that began at UT Austin and has spread across the country. Then we saw the launch of Maker Faire™ to showcase STEAM design in informal learning space. When I went to my first faire 3-4 years ago, I was amazed that there wasn’t tighter articulation between schools, teacher education programs, and what’s going on in this sector.

In schools, "making" is mostly robotics, especially at the secondary level. School libraries may have makerspaces that are more diverse, but there’s very little happening in teacher preparation for how we prepare teachers for these spaces that are proliferating. No two people have the same vision for what you mean when you say makerspace. Whenever you talk about this, it’s so easy to get excited about the 3D printer, laser cutter and other specific tools. At UTeach, we’re more interested in how it transforms what kids are able to do and how teachers are empowered to teach differently. Not to dismiss the tools, but ultimately, what’s so exciting about all of this stuff is how it connects to this lineage of progressive education dating back to Dewey and meaningful, authentic, relevant work. That’s what’s so powerful to me about this whole maker movement. It really champions student voice in a way that I don’t see in any other movement/innovation/fad. How can we replicate that for every kid? One of the biggest hurdles in education and industry is to get kids curious. Makerspaces can get them to a point where they can start wondering.

The maker world and project-based formal education don’t seem to respect each other enough. The maker world which is super auto-didactic, self-sufficient, diy, vibrant and very curious. The maker world sentiment is that schools are going to destroy the maker movement by embracing it and standardizing it. It’s not an unfounded fear. Look at the computer labs in the 90s. The way that education works is in compartmentalizing. My biggest fear is that it becomes a space where you go and do « making » for an hour completely separated from (or only superficially connected to) science, math, language arts, literature, art, etc.

The formal education world is coming from a perspective that we’ve been doing « making » well before Maker Faire started in 2006, but have called it other things like project-based instruction. Colleges of Education see the value in makerspaces, but in public education we have to focus on serving every kid. While the Maker Education Initiative motto is « every kid a maker » colleges of education and educators in general are asking what do we do with kids who aren’t motivated by blinking a light or don’t identify with the notion of making? How does PD play out in these different areas and what does it look like as these spaces develop?

“Do you think that schools/universities would be adopting Makers Spaces if it wasn’t tied to funding?”

These spaces have always existed in universities, but they used to be highly articulated with coursework. Making in a university is usually housed in the college of engineering, which makes sense for digital fabrication and electronics. You were typically a junior before you got to that level of coursework and only accessed the equipment for specific, course related projects. If you talk to industry, a big complaint is that universities are producing engineering graduates who can calculate, but can’t use a screwdriver and a hammer or connect that academic experience to the real world.

A makerspace is more similar to a library type model so it’s open and you can go in and make when/what you want. UT opened a Longhorn Maker Studio and when I went there in November it was full of kids making Christmas presents (like ornaments, a picture frame, and other highly personal artifacts). There’s a lot of class projects, but it’s more about figuring out what they can do with it. That’s what’s exciting.

Something that I see as very similar to the makerspace idea in the College of Science is open inquiry where students choose what they want to learn more about, design an experiment, and analyze results. In UTeach, one of the nine courses is totally dedicated to this process. Instructors have noticed that the hardest part of the process is to get students to become curious. Get students to develop their own questions that can be addressed by experiments. In education, we have identified content, but the gap is how we inspire students to be curious and engaged and motivated and passionate. It’s so well connected in general to how we get students to think and be self-motivated and have internal drive.

“One could argue that Makers spaces are going the way of MOOCs — only reinforcing the privilege and access of middle-class paradigms and still largely unused in lower-income/marginalized communities. If we really belief that Makers spaces improve creativity, critical thinking and STEM, what will it take for the movement to reach a more diverse audience?”

Why I see maker movement as being fundamentally different, is that I see it as hitting on different things, namely on student motivation and constructivist education, with what we know about how students learn best, project-based instruction, and the evolution of progressive education. At the UTeach conference last May, we had several sessions about making in the classroom. It’s important for us is to embed this into regular coursework. Right now, a lot of the robotics and electives are afterschool activities, but in order for this to be truly democratized, we have to make it part of our classes—science and math that every kid takes. NGSS and CCSS math standards demonstrate value for persistent problem solvers, design cycle and implementing inquiry. Makerspaces can support these standards for all students.

As part of the maker strand at our UTeach conference Leah Buechley gave the plenary talk contrasting mainstream maker approaches with tools and techniques designed to support diversity and equality.” This is exactly why we, in education, need to systematically develop opportunities around « making » for a more diverse population, which early indications show is working. We’re already seeing that the demographics of youth-serving maker spaces are much more diverse than that of Maker Faire.

Mike’s One Good Question: How can we use this space to address community needs ? What we’re doing is making things, but why are we making them?

Michael DeGraff is the Instructional Program Coordinator at the UTeach Institute. His work includes coordinating the Instruction Program Review process for all UTeach Partner Sites as well as supporting instructors to implement the nine UTeach courses.Michael has been a part of UTeach since 2001, first as an undergraduate student at UT Austin (BA Mathematics with Secondary Teaching Option, 2005), then as a graduate student (MA Mathematics Education, 2007), and finally as a Master Teacher with UKanTeach at the University of Kansas. He was also instrumental in launching Austin Maker Education.

One Good Question with Susanna Williams: Is Higher Ed the Equalizer We Think?

This post is part of a series of interviews with international educators, policy makers, and leaders titled “One Good Question.” These interviews provide answers to my One Good Question and uncover new questions about education’s impact on the future.

“In what ways do our investments in education reveal our beliefs about the next generation’s role in the world?”

Higher education has seen wholesale disinvestment since 2008. The majority of students in our country attend public universities, and 26% attend community colleges. Liberal arts & research institutions serve a very small population of US students, and their funding challenges are unique. As the economy has recovered, the funding has not returned to state-funded higher education. Part of this is a function of discretionary spending at the state level because very little funding comes from federal government. Most states have mandated spending that has to be accounted for, but higher education is one of the few discretionary lines, so states tend to turn to the public universities and say « charge more tuition. » At the same time as tuition is increasing, we’re getting the message that the full pathway to life is through college attainment. Universities are then seeking outside students—foreign nationals and out-of state students who will pay the sticker price for tuition as opposed to the in-state rates. So there are fewer seats available for lower-income applicants.

Employers then use the college name as a basis for hiring. So community college students are at a disadvantage on the hiring market, unless they are health care assistants, and the hospital has a relationship with their specific college program. Connections become pathways to employment and prosperity.

When we do not fund quality education, yet hold people’s lives accountable as though they have received that education, we’re actually saying that we don’t believe that education is something that everyone in our country should have equal access to. And we’re ok with some people being poor and we’re ok with some people not having access to opportunity.

“How did the funding become discretionary?”

Higher education and public policy hasn’t caught up with modern times. When state constitutions were written, basic education was just K-12 through the 1970s. At that time, you could get a great manufacturing job or vocational training and make solid money. Then the world changed. The only thing slower to change than education is government. There is a strong case for community colleges to be a part of basic education and should be included as K-14 education. The State of Washington’s constitution’s first prioirity is to fully fund basic education, but they’re not meeting basic expectations. Look at funding formulas driven by property taxes and tax code and no one wants to tackle the tax code. It’s not sexy and doesn’t win you elections.

“Who’s actually having this conversation?”

I’m not sure people are connecting the dots. The only way it’s happening is through lawsuits over K-12 education. State legislatures have been held in contempt of court because they haven’t figured it out. That’s another conversation that we don’t want to have. What is it that families do? We need to be asking what does it actually cost to educate a child who does not grow up with the benefit of house with books, afterschool curriculum, print-rich nursery school environment? What does a middle class child have as ancillary benefits? What are the habits that their families inculcate and the culture that they grow up in? How can we provide those standards for all children?

“In our analog/digital divide, higher ed institutions are working feverishly to incorporate new tech tools and communication paradigms into their pedagogy and engagement. Do the tools really matter for this generation? How should post-secondary institutions position themselves for responsive/inclusive engagement?”

With respect to the founding of higher education in Europe, the primary function was to train priests. Higher education today retains the vestiges of that holy process. It is serious and magical and spiritual, and you can’t touch that or dirty that with technology and money is the worst kind of profanity. People keep calling for the end of college. Colorado had a major freakout about MOOCS, which challenges the delivery of higher education. I think there’s a big disruption coming. Competency-based education is going to shift the paradigm and project based learning will change instructional practice. Badges of proficiency will change that option. When we remove the Carnegie credit hour and let students show what they can do, then we no longer need to have institutions as arbitors of confidence.

We say that institution and pedigree matters, yet people still hire based on who they know and how comfortable they feel with that person. Take the example of The Wire and the network of the dealers on the street. That show demonstrates that networks are equally powerful in dark economy and formal economy. Our challenge is to figure out how to teach and give networks to other people. If you win the lottery and leave East Flatbush, and make it to the Ivy’s, there’s no guarantee that you will be able to access the network of the Ivy League. Again, this assumes that access and equity are goals of education. There’s a big divide in education philosophy between those who are warriors for justice through education and those who are gatekeeprs to keep marginalized people out of power structures. I forget that others use education as a sorting tool.

Susanna’s One Good Question: How do we effectively move people to opportunity in our country, if we don’t agree that everyone should have opportunity?

Founder & CEO of BridgEd Strategies, is a lifelong educator and communications specialist with over 15 years of experience as a teacher, administrator, and strategic leader in K-12, higher education, and the philanthropic sector as well as political campaigns. Susanna led marketing, communications, and government relations at Renton Technical College, while also serving as the executive director of the Renton Technical College Foundation. She joined the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation's Postsecondary Success team in 2012 after connecting with the director through a blind message on LinkedIn. Active on Twitter since 2009, Susanna is a strong advocate for the power of social media and the power of networks. A 2011 German Marshall Memorial Fellow, Susanna received a Masters in Education from Bank Street College of Education and a Bachelors in Politics from Earlham College. She lives in her home borough of Brooklyn, New York.