One Good Question

Blog Archives

One Good Question with Kathy Padian: How Leadership Trumps Funding in School System Improvement.

This post is part of a series of interviews with international educators, policy makers, and leaders titled “One Good Question.” These interviews provide answers to my One Good Question (outlined in About) and uncover new questions about education’s impact on the future.

“In what ways do our investments in education reveal our beliefs about the next generation’s role in the world?”

The first thing that comes to mind, is the the disparity amongst different communities and their investments. In a recent meeting about school turnaround, we learned about Camden, NJ, where they spend $26,000 per student in a district with 15,000 students. The majority of us in the room, our heads exploded. Here we are, in a very impoverished state and city where housing prices are rising and we’re still investing around $10,000 per students. It’s mind boggling. When I read that question, I was thinking overall in the US, we don’t invest nearly enough. Kids should have the ability to go to a classroom or education environment from birth or 2-3 years if they want to (not mandatory). In Louisiana we don’t require school until 7, which is a crazy law. There needs to be a much greater investment. We hear all the sound bites about a different type of future and technology based innovation entrepreneurial thinkers etc., yet in many places, (not Camden) we are falling woefully short on the investment side, and education becomes the easiest thing to cut from a budget (especially early childhood education). We’re not putting our money where our mouth is. Defense budget is quadrupling in comparison to education.

“In the post-Katrina New Orleans education landscape, we've seen considerable economic resources invested in outcomes for youth. Which ones have had the greatest game-changing impact? Which investments are replicable for other underperforming urban school communities?”

From where I sit, the greatest game-changing impact wasn’t specifically economic. There was no money that changed things. It was more the ability to restart. In order to get rid of what was generations of complacency, graft, corruption and no real accountability because the “people who were supposed to be holding the district accountable” were part of the graft and corruption. In pre-Katrina New Orleans, if you were able to, you sent your kids to private or parochial schools. If you weren’t able to, there was some relationship between not having the money for private school and lack of grassroots agency to create change. Pre-Katrina, there were absolutely small pockets of schools and folks who were trying to do things differently, but the mentality was, “I can’t save everyone, so I’m going to save this subset of kids.” It seemed so intractable.

Getting to where you remove the massive money suck at the central office, is probably the thing that was the game changer. I don’t know how other cities can replicate that. Does state takeover create that space? Outsiders think that New Orleans education recovery was flooded with funding, but the funding was targeted. New Orleans received a federal investment and FEMA supports to rebuild schools. Like everything in Louisiana, we didn’t hire the right people. We had people with no experience who were hired to manage billion dollar budgets. The money wasn’t managed better, however, or we could have had more buildings or better status for the construction.

“So what made the central office different?”

You need a mix of veteran and newcomer administrators. This is one of the five recommendations in The Wallace Foundation’s brief on the role of district leadership in school improvement. In any existing administration, there are good and hard working team members who, if they had good leadership with visionary direction, they would adapt and be great. You also need people who are coming from the outside (of the district or region) and who have seen a different way of doing things. These two cohorts need to work along side each other. You need that mix: outsiders who come in with some humility and are willing to work with veterans and veterans who want to adapt. Building and guiding such a team requires really strong leadership to get everyone on the same team and working towards the same goal.

Recovery School District was getting there, but now the pendulum has swung the other way. We currently have a super young team with lots of energy who are now starting to try “new ideas” that, in some cases, were the same old ideas from before. Old heads hear these “new ideas” and are loathe to work with the new staffers. This is maddening because there was an opportunity for Orleans Parish to bring the schools back. The bridge building that we began could have continued – to bring the fresh ideas and the institutional knowledge together in the same place. But that’s not happening, and with the new governor, who knows how the legislature will respond. We’re not ready for change, but politics may force the hand.

Kathy’s One Good Question: When are we really going to make the hard decisions about quality? We have had aggressive expansion and replication of homegrown CMOs and lots of discourse about market share, but it’s been at the expense of quality seats for every child.Back to my meeting about Camden, I want to know why aren’t there more women CMO leaders and superintendents? There are women running amazing schools, districts, CMOs who are waiting to expand until they reach perfection, while their male counterparts are growing mediocrity.

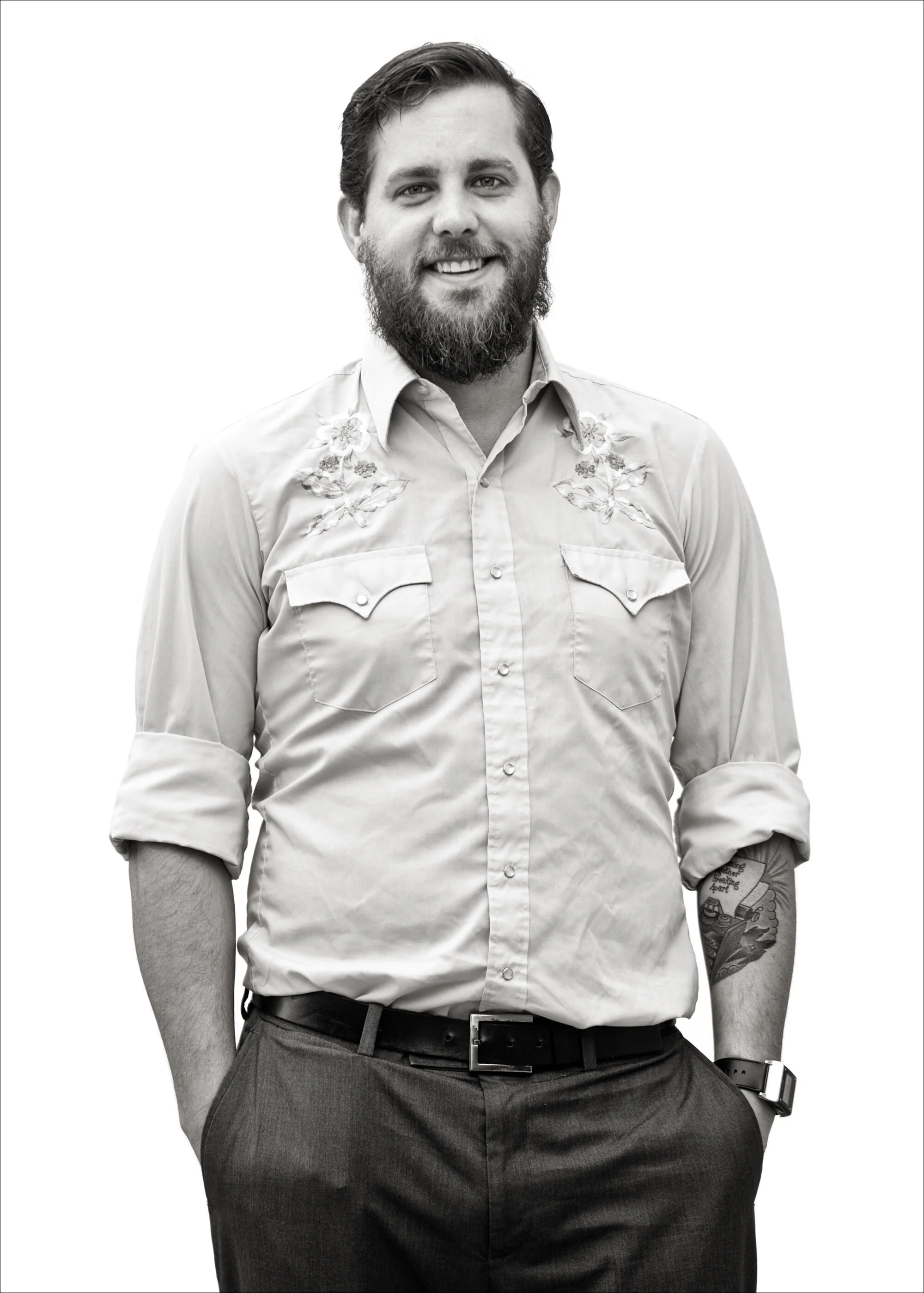

Kathy Padian has more than twenty years of experience in the field of K-12 public education from her start as a classroom teacher to the executive management of schools, non-profit and philanthropic organizations. She is Former Deputy Superintendent at Orleans Parish School Board and is now senior partner at TenSquare focused on improving charter school quality throughout the U.S.; based in D.C. & NOLA. She is thrilled to be the mother of an energetic 7 year old and to serve as a founding Float Lieutenant in the Krewe of Nyx (the largest all female parading Krewe in Mardi Gras history). Background on NOLA schools 2005-2015

One Good Question with John Wood: Teaching the world to read

John Wood photo

This post is part of a series of interviews with international educators, policy makers, and leaders titled “One Good Question.” These interviews provide answers to my One Good Question (outlined in About) and uncover new questions about education’s impact on the future.

“In what ways do our investments in education reveal our beliefs about the next generation’s role in the world?”

Room to Read was founded 15 years ago as a little unknown startup. We boil our belief down to six simple words : World change starts with educated children. We truly believe that if you want to change the future, the biggest no brainer in the world, you start with educating your children. Traditionally, for parents, that means your own children. Those who have been given the gift of education then have an obligation to give back to kids in low-income countries. We have a duty to give back and an opportunity to change things forever. We all have an ancestor who was the one to break the cycle of poverty for our family. Once that cycle is broken, the benefit pays forward for generations. To me, you look at the world today with over 100,000,000 children not in schools, and 2/3 are girls and women. If you want to change the world, then education is the smartest place to start.

“Literacy and primary education have dramatic positive impact on life expectancy, overall health, and ending cycle of extreme poverty in developing nations. Beyond making books and reading accessible, the Room to Read model has created complex local education ecosystems that are highly responsive to local needs. What else does the ecosystem need to be sustainable for all children?”

One of the most important things is that the communities we work with are fully invested in each and every project that we do. It’s not plunking something down for them to use, but co-building something the community is co-invested in. We also need the government to be co-invested in the projects and have some skin in the game as well. Our model is one of local employees, it’s not Americans flying over to do durable projects and telling local people what to do. It’s local community buy-in as employees, volunteers, parents in the planning committee, and then the government providing the teachers and the librarians and paying their salaries. As a result of that ecosystem, and we have the data to prove it, the model is more sustainable over time.

“How are you getting government engagement ? What strategies could other international education NGOs adopt?”

For us, we had to prove that we had a scalable model. Government doesn’t want to work with an NGO unless they have a big vision, a scalable model, resources, and can impact serious scale. That’s what we’ve been able to deliver with the governments. Too many folks want to do one-off projects. What we’re saying is that we can invest impact change at the town, region, even national level.

John's One Good Question: My question is simple. If we know that education is the best way to change the future, and to impact subsequent generations, then why is the world not doing more about the fact that over 750 million people lack basic literacy?

John Wood is the founder of Room to Read. He started Room to Read after a fast-paced and distinguished career with Microsoft from 1991 to 1999. He was in charge of marketing and business development teams throughout Asia, including serving as director of business development for the Greater China region and as director of marketing for the Asia-Pacific region. John continues to bring Room to Read a vision for a scalable solution to developing global educational problems with an intense focus on results and an ability to attract a world-class group of employees, volunteers, and funders. Today, John focuses full-time on long-term strategy, capital acquisition, public speaking, and media opportunities for the organization. John also teaches at the Harvard Graduate School of Education and New York University’s Stern School of Business and serves on the Advisory Board of the Clinton Global Initiative. John holds a bachelor's degree in finance from the University of Colorado and a master’s degree from the Kellogg School of Northwestern University. Follow John on Twitter @JohnWoodRtR.

One Good Question with Chris Plutte: Can Global Understanding Help us Address Race Issues in the US?

This post is part of a series of interviews with international educators, policy makers, and leaders titled “One Good Question.” These interviews provide answers to my One Good Question and uncover new questions about education’s impact on the future.

“In what ways do our investments in education reveal our beliefs about the next generation’s role in the world?”

There’s a genuine interest in wanting to be global but folks don’t know where to start. When you ask someone how they’re working towards the goals of being global citizens, they are very few examples. We’re still a current event on a Friday at 1pm. That’s how schools go global. I don’t think we’re preparing kids for a global society at all. We’re failing at that. We are thinking about right now, but not 2030 or 2045 when we’ll be more connected than we already are. We’re not teaching the kids skills of communication and collaboration across countries. There’s a shift that needs to happen from competition against Finland and Singapore to collaboration with Finland and Singapore. Then we need to work backwards with the skills that young people need to develop for that new economy.

Personally, I come to this from a peace-building lens. How do you bring people together who don’t understand each other and are in perceived conflict with each other? We’re living in a world where people are bouncing up against each other and don’t have the skills to navigate that. Ten to fifteen years ago, we had diplomats sitting in capitals representing our values and cultures to other communities. We’re now side-by-side engaging and we don’t know how to do that intercultural communication. We won’t be able to do that until we engage whole communities—parents and educators to become global citizens. Give them the tools, experience, and opportunities to inquire about how the world is outside of their own city. Then they can be inspired to share those with the young people that they’re educating. The investment is really with the adults right now as much as with the students.

“You’re the first American educator in this interview series to bring up peace as a function of education.”

When we talk about race, there’s a conversation there about peace, but we’re looking for peace within our communities. I’m curious about how global can help local. I’m stuck on Einstein’s idea that no problem can be solved in the conditions in which it was created. The idea that you have to leave the environment to solve the problem. I wonder if there’s an opportunity to expand on that and talk about race issues and conflict issues. There’s such massive Islamophobia in the US. At Global Nomads Group, we focus on linking US schools and Muslim-majority countries. Part of it is building compassion and empathy for one another. That’s a muscle that gets developed. It’s perhaps easier to have a conversation around Islamophobia than race issue in your own community. Can you build that muscle globally and then pivot and use it to address race issues in the US? As an organization, we’re trying to explore that possibility.

When we think of global citizenship in the US, we think about teeing up Americans to be global citizens. But you can’t be a global citizen by yourself. There’s a perspective called Ubuntu-- I am me because you are you. You need the « other » to be a global citizen. Right now it’s a taking, how can we take from other places to be global? It’s not about taking. It’s about navigating within an ecosystem with others who are also global citizens and navigating yourself with different experiences. It’s a long-play. It has to be cultivated and integrated over years.

“What are the first steps to change?”

I need to articulate to people what the world actually is and be a bit of a futurist. When the educator or administrator sees themselves as a global citizen, then they can champion it. Peace Corps, Army Brats, and Third Culture Kids seek out Global Nomad Group to impact their classrooms. The big question is how do you move beyond those converted communities and get the larger community engaged in demanding it? That’s what we need right now. We need larger communities demanding it for their children and their schools in an authentic real way.

“So many educators in urban settings regard this work as esoteric or enrichment. How do you start from that perspective?”

Where we are, you have to work with the willing : networks, districts and charters who are willing to partner with you and can be an example to others. People need to be able to have some type of anchors and understand that they can do that too. I certainly felt in my fellowship that I was with these rock star educators who are trying to get kids to graduate high school. Who am I to say, By the way, you should also go global. I struggle with this. We have a problem here in the US, but in comparison to rural schools that meet under trees in the blistering sun, we also live an extraordinary opportunity. We can create a community in which people are engaging globally and that will help their local communities. That’s how I approach it with those folks: Problem-solving. For me, if you would weave that together with problem-solving and peace-building and race issues—that woven together often will resonate with the ed reform community. Not everyone, but enough entry points to move away from being the fringe in order to get a small place at the table. And we need those entry points right now.

“With Global Nomads group, you answered one of the fundamental questions about access to get youth in developing nations connected with their global peers. What student-led action are you seeing for youth on both sides of the experience as a result of their participation?”

All of our programs are project-based. So when you’re paired with a school, you have to identify a problem within your community that your going to help answer based on this program. We had a group in Pakistan focus on girls’ education and girls in their community not going to school. In the US, it was a recycling and environmental program for trash in their community. We work together and compare and contrast and offer ideas to each other. The results for the Pakistan students were that they actually did a community awareness about girls’ education, met with families of the girls, raised money and got scholarships for local schools to get the girls enrolled in schools. Just last week, a US school who is connected in Gaza actually planned a whole week(!!) to do a program around educating their community on Islam. The action was really inspired by the young people in the US hearing from their Palestinian counterparts on how their own stereotypes and stigmas impacted their community. That was a result of their programs.

Chris' One Good Question: How do I get global citizenship to be as important as trigonometry? How do I get the broader ed reform community engaged and demanding this?

Chris Plutte is the Co-Founder and Executive Director of Global Nomads Group (GNG). Founded in 1998, GNG is an international non-profit whose mission is to foster dialogue and understanding among the world's youth. In 2008, Plutte worked overseas for Search for Common Ground (SFCG) as Chief of Party and Country Director for Rwanda. He opened and directed all of SFCG's programs in the country and oversaw cross border initiatives in the Democratic Republic of Congo and Burundi. During his two-years in the African Great Lakes region, Plutte introduced innovative programs for peace building using technology in the classroom and secured new funding for program growth and expansion. He rejoined GNG in 2010 as the Executive Director. Plutte received his B.A. in International Communications from the American University of Paris.

When Women Succeed, the World Succeeds. #IWD2016

In honor of International Women's Day/ Journée des Droits des Femmes, a look back at Dr. Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka's talk "When women succeed, the world succeeds."

We need to get decision makers to stop seeing women as the problem or charity case. We will not overcome inequality or poverty or sustainable peace if we do not improve the lives of women. There are only 20 women heads of state in the world. if we had more female leaders we would not be in this state. Women are part of creating the world we all want. We have to invest in women. When you leave women out, you compromise the rest of the nation.

What it will take for more governments, institutions, schools, etc. to understand that improving the lives of girls and women will increase opportunities for the entire society?

One Good Question with Vania Masias: How to Disrupt the Victim Mentality when Investing in Youth Agency.

This post is part of a series of interviews with international educators, policy makers, and leaders titled “One Good Question.” These interviews provide answers to my One Good Question (outlined in About) and uncover new questions about education’s impact on the future.

“In what ways do our investments in education reveal our beliefs about the next generation’s role in the world?”

One of my dreams is that our methodology through arts becomes public policy in the public schools. That’s my dream because every day I see the empowerment that our youth leaders have thanks to dance or arts. I think the government, and people who have never danced, have no idea how powerful this tool is. I just came back from Trujillo, another state in Peru. I went with one of the “kids” who is 21 and has been with Angeles D1 for 5 years. Five years ago, he was in to gangs. He finished his public school, but school gave nothing to him. He was emotionally devastated. He was into drugs, gangs, and jail. Today, he just did a Tedx talk and he’s a leader of more than 200 kids in one of the most difficult communities in our region. He is a teacher and one of the best dancers in our company. He learned to know himself and to start loving himself just as he is.

When you dance you are just you — you are not your name, the daughter of so-and-so, the girl that went to this school. When I dance, I am not in a social level, it’s just me, my soul, myself, my truth. That’s really powerful.If I were to tell people where to invest in education: creativity, culture, arts. I believe, because I dance and I choreograph, that every human being has a jewel. We are so beautiful on the inside and through arts it's a beautiful thing to bring that beauty out. Our education system was focused on the British empire, and that established norms around knowledge. In that system, if you’re not good with math or literature, you’re kind of a pariah. At Angeles D1, our focused education gives empowerment to the kids so teachers can see their potential and bring it out. The arts allows you to bring those other gifts to the forefront.

“The Angeles D1 model has been heavily informed by the youth participants, their needs and vision. Your lessons on youth agency were very organic. How would you recommend that adults planning programs for marginalized youth intentionally incorporate these lessons into their work?”

The first advice I will give is to get rid of guilt. Growing up in a country where you have everything and then you see others who have nothing, that’s difficult. One big mistake I made when I started the program, was that I thought I had to give everything to the youth without asking anything in return. That mentality creates beggars and welfare dependency. Don’t give the toys, teach them how to make the toys so that, afterwards, they can make it and sell it and it’s a development. Otherwise, they will say “Poor me, I’m a victim,” and they will keep begging. You further the stigma that says you are poor, you won’t make it, so I’m solving your life. I had to learn that and it was kind of difficult. I felt guilt all the time and they knew that. It was not healthy.I remember one day when 4 or 5 of the first generation dancers started stealing from the company. That day, everything changed. They weren’t stealing things, they stole the choreography that we made as a group, and they went somewhere else and charged for it. I kicked them out of the group because that didn’t respect D1 values.

Last week, on the way to Trujillo for the Tedx talk, we saw the same kids who stole from us. They were in the exact same place, dancing under the same street light that they were 10 years ago. I just turned and looked at our youth leader and started crying. OMG. There we were, a few blocks from the airport and he’s going to speak to a crowd of 200 professionals about his work yet we saw his peers in the exact same place. We said nothing to each other. It was evident. They made the decision to not grow. They wanted that life. They just wanted to stay there. It’s not wrong. It’s not good. It’s just their decisions.When we want to communicate, we only see our side of things. A question that helped me was “How can I reach them and generate confidence?’ I decided to go through urban culture to reach our youth. I put myself in their place. I tried to see what are they looking at and understand what’s gong on with them. I hadn’t studied psychology, sociology, or anthropology to know what was going on with them. I believed in dance. When they moved, they were communicating something to me. So with that information, I could understand what they were seeing. They put their eyes always down, they would never look at me. That gave me a lot of information and then I designed everything around that. Let’s do clowning and get them to feel ridiculous. We never saw the other, to see and look is different. We’re in such a rush, we never see each other. When that happened, everything changed.

Vania’s One Good Question: One of my lead dancers dreams of becoming mayor of his hometown, Tumbes, in northern Peru. I see D1 as “The Hobbit” for him, a safe place that will support and encourage him. As social organizations, can we develop the leaders of tomorrow to be pure and uncorrupted?

Vania Masias was born in Lima, Peru. She graduated from Universidad del Pacifico and is a professional ballerina. She was the principal ballerina in the municipal ballet for 7 years, with the most important roles in the classical repertory. She then began a modern dance career with the Yvonne Von Mollendorf company, with international residencies in Europe and the Caribbean. Vania was a principal ballerina in the National Ballet of Ireland and was selected for Cirque du Soleil. In 2005, for family reasons, she returend to Lima and founded the Asociación Cultural D1 (de uno) and is currently the Executive Director.

One Good Question with Mike DeGraff: Are Schools Destroying the Maker Movement?

This post is part of a series of interviews with international educators, policy makers, and leaders titled “One Good Question.” These interviews provide answers to my One Good Question and uncover new questions about education’s impact on the future.

“In what ways do our investments in education reveal our beliefs about the next generation’s role in the world?”’

There was a call for 100,000 STEM teachers in the US, and since then there have been tons of initiatives, and related funding, to respond to the need (some say too much). UTEACH is a very constructivist-oriented teacher education program for STEM teachers, that began at UT Austin and has spread across the country. Then we saw the launch of Maker Faire™ to showcase STEAM design in informal learning space. When I went to my first faire 3-4 years ago, I was amazed that there wasn’t tighter articulation between schools, teacher education programs, and what’s going on in this sector.

In schools, "making" is mostly robotics, especially at the secondary level. School libraries may have makerspaces that are more diverse, but there’s very little happening in teacher preparation for how we prepare teachers for these spaces that are proliferating. No two people have the same vision for what you mean when you say makerspace. Whenever you talk about this, it’s so easy to get excited about the 3D printer, laser cutter and other specific tools. At UTeach, we’re more interested in how it transforms what kids are able to do and how teachers are empowered to teach differently. Not to dismiss the tools, but ultimately, what’s so exciting about all of this stuff is how it connects to this lineage of progressive education dating back to Dewey and meaningful, authentic, relevant work. That’s what’s so powerful to me about this whole maker movement. It really champions student voice in a way that I don’t see in any other movement/innovation/fad. How can we replicate that for every kid? One of the biggest hurdles in education and industry is to get kids curious. Makerspaces can get them to a point where they can start wondering.

The maker world and project-based formal education don’t seem to respect each other enough. The maker world which is super auto-didactic, self-sufficient, diy, vibrant and very curious. The maker world sentiment is that schools are going to destroy the maker movement by embracing it and standardizing it. It’s not an unfounded fear. Look at the computer labs in the 90s. The way that education works is in compartmentalizing. My biggest fear is that it becomes a space where you go and do « making » for an hour completely separated from (or only superficially connected to) science, math, language arts, literature, art, etc.

The formal education world is coming from a perspective that we’ve been doing « making » well before Maker Faire started in 2006, but have called it other things like project-based instruction. Colleges of Education see the value in makerspaces, but in public education we have to focus on serving every kid. While the Maker Education Initiative motto is « every kid a maker » colleges of education and educators in general are asking what do we do with kids who aren’t motivated by blinking a light or don’t identify with the notion of making? How does PD play out in these different areas and what does it look like as these spaces develop?

“Do you think that schools/universities would be adopting Makers Spaces if it wasn’t tied to funding?”

These spaces have always existed in universities, but they used to be highly articulated with coursework. Making in a university is usually housed in the college of engineering, which makes sense for digital fabrication and electronics. You were typically a junior before you got to that level of coursework and only accessed the equipment for specific, course related projects. If you talk to industry, a big complaint is that universities are producing engineering graduates who can calculate, but can’t use a screwdriver and a hammer or connect that academic experience to the real world.

A makerspace is more similar to a library type model so it’s open and you can go in and make when/what you want. UT opened a Longhorn Maker Studio and when I went there in November it was full of kids making Christmas presents (like ornaments, a picture frame, and other highly personal artifacts). There’s a lot of class projects, but it’s more about figuring out what they can do with it. That’s what’s exciting.

Something that I see as very similar to the makerspace idea in the College of Science is open inquiry where students choose what they want to learn more about, design an experiment, and analyze results. In UTeach, one of the nine courses is totally dedicated to this process. Instructors have noticed that the hardest part of the process is to get students to become curious. Get students to develop their own questions that can be addressed by experiments. In education, we have identified content, but the gap is how we inspire students to be curious and engaged and motivated and passionate. It’s so well connected in general to how we get students to think and be self-motivated and have internal drive.

“One could argue that Makers spaces are going the way of MOOCs — only reinforcing the privilege and access of middle-class paradigms and still largely unused in lower-income/marginalized communities. If we really belief that Makers spaces improve creativity, critical thinking and STEM, what will it take for the movement to reach a more diverse audience?”

Why I see maker movement as being fundamentally different, is that I see it as hitting on different things, namely on student motivation and constructivist education, with what we know about how students learn best, project-based instruction, and the evolution of progressive education. At the UTeach conference last May, we had several sessions about making in the classroom. It’s important for us is to embed this into regular coursework. Right now, a lot of the robotics and electives are afterschool activities, but in order for this to be truly democratized, we have to make it part of our classes—science and math that every kid takes. NGSS and CCSS math standards demonstrate value for persistent problem solvers, design cycle and implementing inquiry. Makerspaces can support these standards for all students.

As part of the maker strand at our UTeach conference Leah Buechley gave the plenary talk contrasting mainstream maker approaches with tools and techniques designed to support diversity and equality.” This is exactly why we, in education, need to systematically develop opportunities around « making » for a more diverse population, which early indications show is working. We’re already seeing that the demographics of youth-serving maker spaces are much more diverse than that of Maker Faire.

Mike’s One Good Question: How can we use this space to address community needs ? What we’re doing is making things, but why are we making them?

Michael DeGraff is the Instructional Program Coordinator at the UTeach Institute. His work includes coordinating the Instruction Program Review process for all UTeach Partner Sites as well as supporting instructors to implement the nine UTeach courses.Michael has been a part of UTeach since 2001, first as an undergraduate student at UT Austin (BA Mathematics with Secondary Teaching Option, 2005), then as a graduate student (MA Mathematics Education, 2007), and finally as a Master Teacher with UKanTeach at the University of Kansas. He was also instrumental in launching Austin Maker Education.

One Good Question with Ejaj Ahmad: Why We Should Build Leadership Instead of Leaders.

This post is part of a series of interviews with international educators, policy makers, and leaders titled “One Good Question.” These interviews provide answers to my One Good Question and uncover new questions about education’s impact on the future.

“In what ways do our investments in education reveal our beliefs about the next generation’s role in the world?”

Bangladesh became independent in 1971, and while the founding leaders were visionaries, I’m not sure they thought deeply about the kind of education that the next generation would need to take the country forward? That’s my gut feeling. Once you ask this One Good Question, you are forced to somehow link your input and process with the output that you’re seeking. As a country, we have not yet really explored the educational foundation that we need to put in place to create an inclusive and just society. I say this because we see it every day how the divided education system, namely English medium (British curriculum), Bangla medium (national curriculum) and Madrassa (Islamic studies curriculum), contributes to communal tension and violent politics. Young people from these divergent education streams grow up with differing values and ideologies and they rarely interact with people from other educational backgrounds. This is one of the root causes of many of the divisions we see in Bangladesh today. Moreover, the curriculum in school, college, and university relies primarily on rote learning which doesn’t foster creativity and critical thinking in students. As a result, most young people enter the job market with little prior training in problem solving.

At Bangladesh Youth Leadership Center, we aspire to see the next generation exhibit values of inclusiveness, tolerance, and compassion. We also want to see them develop strong critical thinking skills so that they can question deeply held values and assumptions. Therefore, our organization runs after-school leadership programs that unite high school, college, and university students from the three different educational systems and provide them problem solving, leadership, and communication skills and engage them in the community where they can translate their learning into action by designing and implementing service projects.

“You are committed to developing youth leadership and agency. Why does it matter?”

This question is powerful because more than 52 percent of Bangladesh’s population of 160 million is below the age of 25. Traditionally, we have always equated leadership with position. We use the word ‘leader’ and ‘leadership’ interchangeably although intuitively we know that they are not the same. Leader is a person or a title, whereas leadership is an activity, which can be exercised from a position of authority or without a position of authority. Now imagine if every single young person perceived leadership as an activity and not as a position then the impact this shift in thinking can have in society. Young people don’t have titles and they don’t occupy public office. However, if they believe that they don’t need a title to exercise leadership and bring change then this sense of agency can have tremendous impact on society. We will no longer be waiting for elected officials to solve our problems; we can take ownership of our part of the problem and do our bit to make progress in our community.

Our youth leadership programs also take young people on a journey of self-exploration, which we also feel is critical for the world today. We need to help young people ask difficult questions, reconcile multiple identities and work across religious and cultural boundaries. This is especially relevant in today’s world where most of our conflicts happen due to differing values and identities. Yes, you are a Bangladeshi, or an Indian, or an American. But you are also a human being. What does it mean to be a human being in the 21st century? What are some of the values that we can all share across nationalities, cultures, and religions? I believe that good leadership education can make people curious and humble. If we can all learn to reframe our truths as assumptions and not hold a monopoly on what we believe to be true, I think we can do a better job of getting along with each other despite our differences.

Ejaj’s One Good Question: What values and habits from the past do you need to carry into the future? What values and habits were once useful but are no longer so? In other words, which part of our cultural DNA do we need to preserve and which part do we need to discard to create a better world, both for us and for the ones we love?

Ejaj Ahmad is an entrepreneur and an educator of leadership, who speaks and advises globally on leadership issues. He is the founder and president of Bangladesh Youth Leadership Center (BYLC), a nonprofit that aims to create a more inclusive, tolerant, and just society by training the next generation of home-grown leaders. Ejaj holds a master’s in public policy from Harvard University and a master’s of arts with honors in economics from St. Andrews University.

One Good Question with Tom Vander Ark: Can Design Thinking & Rethinking Scale Boost Ed Equity?

This post is part of a series of interviews with international educators, policy makers, and leaders titled “One Good Question.” These interviews provide answers to my One Good Question and uncover new questions about education’s impact on the future.

“In what ways do our investments in education reveal our beliefs about the next generation’s role in the world?”

We’ve inherited a sedimentary system made up of a series of 100 years of laws and policies and practices that for us in the US are federal, state, and local. This is in contrast to an engineered system designed to produce a set of outcomes. So, that’s the first problem: our investments, speaking about our public education system writ large, is this product of a democratic process, and not a design system. It’s many and mixed intentions, it’s compromises both good and bad, it’s consequences both intended and unintended, working itself out over time.

The US has a number of anachronistic fixations with local control and reliable and valid assessments. This fixation has the advantage of vesting investments closest to the kids, but the disadvantage of it is linking it to community wealth. This is a great example of a well-intentioned design principle that has produced outrageous inequities in US education. Education funding and, to some extent, quality are now zip code specific because we vested power in local governments.When Arne Duncan announced his departure as Secretary of Education, I wrote a blog post suggesting that we mark that day as the end of standards based reform. From Dick Reilly to Arne Duncan, we had an unusual 20-year arc in the US, where federal government had unusually strong influence from a policy (NCLB) and investment standpoint (AARA, Race to the TOP). It was a great moment in US education that marked a national, bipartisan consensus for equity. As a country, we could no longer sit by and accept chronic failure for our nation’s children.

NCLB was designed as a framework for school accountability to make sure that every family had access to good educational options. In retrospect, almost everyone agrees that the steps and measures used were flawed, but if we had used an iterative development process -- kept what was good and fixed the obvious problem -- the country would be in a better place. One of the problems with NCLB, was that when faced with a choice between measuring proficiency or measuring growth, we latched on to proficiency because it was easy to measure with valid assessments. We largely ignored growth in the law and now we can see the consequences of it. NCLB had a strong focus on getting underperforming kids to grade level which created two unintended consequences: discouraged schools from teaching students who were furthest behind (over age, undercredited), and weaker administrators fixated on the test. Rather than offering a rich, full, inspiring education, they offered test prep. Not only did that not produce lasting academic results for kids, it led to educators trying to game the test, with examples of cheating and embezzlement in the worst cases.

“In the past few years we’ve seen funders, media, and eventually schools rally around the next big tech innovation (1:1, MOOC, coding, etc). How much does the next big tool matter for lasting academic outcomes for all students?”

The reason that I’m so passionate about public education and investment in innovation is because I think that it’s the fastest path to quality and access to quality in the US and internationally. In my previous Ed Reformer blog, I wrote about education reform, making the system that we have better. Getting Smart reflects the new imperative, for every family and neighborhood around the world, to get smart fast. Innovation is critically important to improving access and quality. It’s why I’m really optimistic that things will get better, faster in the US and accelerate international change as well.In the US, innovation investment allows us a design opportunity. The design experience that I’m most passionate about, is people who are conceptualizing LX+IT (learner experience + integrated information technology). They’re not just developing new school models but also integrating information systems and student access devices.

We’re still in the early innings now of new tools and new schools. There are thousands of good new schools, but there are only dozens of schools that are doing this fundamental design work of reconceptualizing learning environments and learning sequences and the tools that go with it. This is the opportunity of our time: to find ways to scale both the work and the number of folks benefitting from it worldwide.Internationally, we have the first chance in history to offer every young person on the planet a great education. When we first started investing in scalable models in the US, funders and founders had grand ambitions that assumed linear replication. Over time, we’ve learned that scaling nationally or internationally is much harder than maintaining strong regional programs and outcomes. We’re starting to see a shift in replication and inspiration across geographies. Take Rocketship for example. They run an amazing model that everyone has flocked to see in the past few years. Among the visitors, were two young MBAs from Johannesburg, who took the lessons learned from Rocketship and created SPARK Schools ins Johannesburg. SPARK is as good a blended learning model as I’ve seen anywhere on the planet. Rocketship didn’t have to cross the ocean for that to happen and now students in South Africa are benefitting from a model that was created in the US.Summit Public Schools has taken a different approach to scaling ideas before scaling schools. This year they have about 19 school partners with their Basecamp model and next year it might be 10 times as many. They have created a powerful Personalized Learning Platform, partnered with Facebook and Stanford to figure out how to scale it broader use, and now team with schools across the country to implement this pedagogy into existing models. We hope that hundreds of schools benefit from their fundamental design work. Seeing these types of growth gives me a tremendous sense of optimism that things can get better worldwide faster than most people realize.

Tom’s One Good Question: Will we actually achieve equitable education access? I’m concerned that things will get better faster for young people who have engaged and supportive adults in their lives. I’m worried about young people that don’t have engaged parents/adults in their lives. Parents who get powerful learning are raising confident, equipped well-informed young people.

Tom Vander Ark is author of Getting Smart: How Digital Learning is Changing the World, Smart Cities That Work for Everyone: 7 Keys to Education & Employment and Smart Parents: Parenting for Powerful Learning. He is CEO of Getting Smart, a learning design firm and a partner in Learn Capital, an education venture capital firm. Previously he served as the first Executive Director of Education for the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Tom served as a public school superintendent in Washington State and has extensive private sector experience including serving as a senior executive for a national public retail chain.

One Good Question with Susan Baragwanath: The Only Way to Break Cycle of Poverty.

This post is part of a series of interviews with international educators, policy makers, and leaders titled “One Good Question.” These interviews provide answers to my One Good Question and uncover new questions about education’s impact on the future.

“In what ways do our investments in education reveal our beliefs about the next generation’s role in the world?”

I have never been into deep thinking on education and I am not much of a philosopher. As a practitioner for 37 years I saw immense change from rote learning to the touch of an iPad. Show me a young person who knows the times tables and can write a sentence in the imperfect tense? But does it matter when they can use a calculator and Google ? As a teacher I have always felt it was my duty to challenge a student to believe that they could do anything they wanted. It was up to me to provide the mechanism so they could achieve to the best of their ability. But now, in the 21st century, what mechanism is it exactly?

There has been huge investment in technology in recent years. This has facilitated both teaching and learning in ways that we previously couldn’t imagine. The change is so dramatic that the traditional teacher now struggles to keep up. We used to joke we needed to be ‘a page ahead of the kids’. Now the joke is on us. Older teachers, with all their wisdom, are so many volumes behind social media, fantasy games, apps etc etc they will never catch up. I see colleagues still trying to put coins into parking meters while a kid is paying with his smartphone.

Many countries have national curriculums and the Education Ministries are given a sum which is then passed on down the line eventually ending up in a school for implementation. Those curriculums which were once worked on by very clever and sophisticated people are now struggling in this technological world. Change can be slow and national curriculums can easily end up a dinosaur in their relevance to the next generation. But yet the poor teacher has to implement it and will have a performance review based upon it and may be under the regime of merit pay.

Perhaps we should distinguish between policy and law. The law in most countries is that every child is entitled to basic formal education for a number of years. But government policies create inequities in implementation of those laws. It can also depend on who is in power at the time and if they allow policy to take over. Most countries manage to run reasonable schooling systems within the constraints of bureaucracies. But one terrible example of a country that doesn’t [run a reasonable schooling system] is Yemen. Pre-1994, they had a half decent school system left over from the British. But then the President of the day said that young people didn’t have to go to school anymore. In other words basic formal education was ‘off’. One of the results is that the Yemen is the most dangerous and shambolic country on earth. Young people who should have had the benefit of a basic formal education now appear on our TV screens wielding guns and chopping off peoples heads.If we don't believe in investment and follow the law and make sure our teachers are given every assistance possible to be up with the play in the digital world, then we should remember the example of extreme and utter chaos of the Yemen, because it can get that bad.

“We have so many marginalized youth (teen parents, adjudicated youth, etc) who need different supports to access mainstream culture in order to break the cycle of poverty. What role can education — in and out of school — play to support them?”

In my experience the only way to actually bring a marginalized young person out of the cycle of poverty they live in, is to provide wraparound services via the school. In one college where I worked (the poorest in NZ with the highest Pacifika population at the time) we tried all manner of things to improve educational achievement. Most of it didn’t work because students came to school hungry and there was no government sponsored food program. You cannot teach a hungry child. The family would often be in crisis and children were regularly bashed up by angry or drunk parents who had no work. Communicable diseases (yes, even in beautiful, peaceful New Zealand) was rife. Scabies, boils, rheumatic fever, tuberculosis – I saw it all. Try to teach a troubled child from that background the history of the Tudors. You may as well bark against thunder.

In this extreme case, food, pastoral care, health care and education in that order became a solution to the problem of marginalized youth. It sounds easy, but I received a letter from the Minister of Education forbidding (strong word that) me to pay for food out of the ‘education’ budget. I was publically scolded by officials from the Department of Health for ‘making a scene’ over a scabies outbreak affecting 70% of the 800 students as they said that ‘scabies didn’t happen in winter’. It most certainly did as I and other teachers got it. It became so bad (many students became infected and hospitalized) they considered calling in the military. The blind eye approach to ‘no scabies in winter’ cost the country buckets of money to get it under control. It was real head in the sand stuff. I solved the pastoral care problem by hiring retirees who were not brain dead at 65 but tired of classrooms full of kids who were too distressed to learn anything.

Eventually in my own little world I managed to shame, cajole, shout, stamp etc and I got all those things above that broke the cycle. It took me ten very long years and I probably neglected a lot of other things including my own children (who thankfully have grown up into amazing adults) but you need to ask the question – why did it have to be so difficult and take so long ?

Once you get over that, education is filling that enquiring mind. And it is a joy to see the fruits of your labour.

Susan’s One Good Question : I am still thinking about it!

Dr. Susan Baragwanath works as an independent consultant. She was a career secondary school teacher and administrator who taught internationally. Dr. Baragwanath is the founder of He Huarahi Tamariki Schools, Maori for ‘a chance for children’. Her program plan was to provide basic formal education and training for teen parents to graduate from high school. These include high quality pre-schools. The highly acclaimed schools were honored and became models, replicated in more than 50 locations around New Zealand.

One Good Question with Susanna Williams: Is Higher Ed the Equalizer We Think?

This post is part of a series of interviews with international educators, policy makers, and leaders titled “One Good Question.” These interviews provide answers to my One Good Question and uncover new questions about education’s impact on the future.

“In what ways do our investments in education reveal our beliefs about the next generation’s role in the world?”

Higher education has seen wholesale disinvestment since 2008. The majority of students in our country attend public universities, and 26% attend community colleges. Liberal arts & research institutions serve a very small population of US students, and their funding challenges are unique. As the economy has recovered, the funding has not returned to state-funded higher education. Part of this is a function of discretionary spending at the state level because very little funding comes from federal government. Most states have mandated spending that has to be accounted for, but higher education is one of the few discretionary lines, so states tend to turn to the public universities and say « charge more tuition. » At the same time as tuition is increasing, we’re getting the message that the full pathway to life is through college attainment. Universities are then seeking outside students—foreign nationals and out-of state students who will pay the sticker price for tuition as opposed to the in-state rates. So there are fewer seats available for lower-income applicants.

Employers then use the college name as a basis for hiring. So community college students are at a disadvantage on the hiring market, unless they are health care assistants, and the hospital has a relationship with their specific college program. Connections become pathways to employment and prosperity.

When we do not fund quality education, yet hold people’s lives accountable as though they have received that education, we’re actually saying that we don’t believe that education is something that everyone in our country should have equal access to. And we’re ok with some people being poor and we’re ok with some people not having access to opportunity.

“How did the funding become discretionary?”

Higher education and public policy hasn’t caught up with modern times. When state constitutions were written, basic education was just K-12 through the 1970s. At that time, you could get a great manufacturing job or vocational training and make solid money. Then the world changed. The only thing slower to change than education is government. There is a strong case for community colleges to be a part of basic education and should be included as K-14 education. The State of Washington’s constitution’s first prioirity is to fully fund basic education, but they’re not meeting basic expectations. Look at funding formulas driven by property taxes and tax code and no one wants to tackle the tax code. It’s not sexy and doesn’t win you elections.

“Who’s actually having this conversation?”

I’m not sure people are connecting the dots. The only way it’s happening is through lawsuits over K-12 education. State legislatures have been held in contempt of court because they haven’t figured it out. That’s another conversation that we don’t want to have. What is it that families do? We need to be asking what does it actually cost to educate a child who does not grow up with the benefit of house with books, afterschool curriculum, print-rich nursery school environment? What does a middle class child have as ancillary benefits? What are the habits that their families inculcate and the culture that they grow up in? How can we provide those standards for all children?

“In our analog/digital divide, higher ed institutions are working feverishly to incorporate new tech tools and communication paradigms into their pedagogy and engagement. Do the tools really matter for this generation? How should post-secondary institutions position themselves for responsive/inclusive engagement?”

With respect to the founding of higher education in Europe, the primary function was to train priests. Higher education today retains the vestiges of that holy process. It is serious and magical and spiritual, and you can’t touch that or dirty that with technology and money is the worst kind of profanity. People keep calling for the end of college. Colorado had a major freakout about MOOCS, which challenges the delivery of higher education. I think there’s a big disruption coming. Competency-based education is going to shift the paradigm and project based learning will change instructional practice. Badges of proficiency will change that option. When we remove the Carnegie credit hour and let students show what they can do, then we no longer need to have institutions as arbitors of confidence.

We say that institution and pedigree matters, yet people still hire based on who they know and how comfortable they feel with that person. Take the example of The Wire and the network of the dealers on the street. That show demonstrates that networks are equally powerful in dark economy and formal economy. Our challenge is to figure out how to teach and give networks to other people. If you win the lottery and leave East Flatbush, and make it to the Ivy’s, there’s no guarantee that you will be able to access the network of the Ivy League. Again, this assumes that access and equity are goals of education. There’s a big divide in education philosophy between those who are warriors for justice through education and those who are gatekeeprs to keep marginalized people out of power structures. I forget that others use education as a sorting tool.

Susanna’s One Good Question: How do we effectively move people to opportunity in our country, if we don’t agree that everyone should have opportunity?

Founder & CEO of BridgEd Strategies, is a lifelong educator and communications specialist with over 15 years of experience as a teacher, administrator, and strategic leader in K-12, higher education, and the philanthropic sector as well as political campaigns. Susanna led marketing, communications, and government relations at Renton Technical College, while also serving as the executive director of the Renton Technical College Foundation. She joined the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation's Postsecondary Success team in 2012 after connecting with the director through a blind message on LinkedIn. Active on Twitter since 2009, Susanna is a strong advocate for the power of social media and the power of networks. A 2011 German Marshall Memorial Fellow, Susanna received a Masters in Education from Bank Street College of Education and a Bachelors in Politics from Earlham College. She lives in her home borough of Brooklyn, New York.

One Good Question with J.B. Schramm: Is College Still Relevant?

This post is part of a series of interviews with international educators, policy makers, and leaders titled “One Good Question.” These interviews provide answers to my One Good Question and uncover new questions about education’s impact on the future.

“In what ways do our investments in education reveal our beliefs about the next generation’s role in the world?”

Every school success paradigm I’ve seen involves similar components: excellent educators, school leaders, data and measurement, standards, etc.—but what you never see is “students” as part of the solution. We have this sense that students are vessels into which education is to be poured. In order to move forward in our communities, we need young people from our communities to take charge. They need to have confidence and be equipped as critical thinkers, problem solvers, strategists, and risk takers. They need the motivation to challenge power structures and be problem solvers in the broader community. We don’t win, and our nation doesn’t become a more just place, simply by informing students. We need to offer them the responsibility to take charge of their education and future.The fact is, young people are most influenced by their peers. Young people today are taking responsibility for more and more parts of their lives, either because adults are abnegating obligations, or because technology is giving youth more opportunity to control their own communication and networks. Young people influence young people, tremendously. We are missing a huge opportunity when we define students as the objects of education. The key that we need in our investments is to show that young people can be drivers of their education. They can take charge of improving achievement in their schools. The paradigm changes when you start with the premise that the young people are on your side, that they can be driving education gains not only for themselves but also for their classmates.I learned these lessons working at College Summit, the nonprofit championing student-driven college success. They coined the phrase #PeerForward, which means to find and train a community’s most influential students in college access and leadership so that they run campaigns with their peers to file FAFSA, apply to college, and explore careers. In this model, the peers are owning the outcomes, not just following adult voice. That’s a very powerful model. We all care more when we own something. When you’re talking about under-resourced institutions, the most powerful resource that schools need is already there in abundance – the students!! They can solve their problems. They want to achieve and they want to be challenged. For teenagers especially, just when they are hungry for greater challenge, we so often keep them in the same sort of structure as elementary school. Let’s take off the training wheels and give them the chance to take on bigger challenges.

“Given all of the contemporary discourse about the ways that traditional K-12 education is not preparing students for the new global economy, is college still relevant?”

A year ago, I co-authored a white paper with Andy Rotherham and Chad Aldeman that outlines today’s post-secondary paradox. On the one hand, college is more valuable than ever. In immediate term the wage premium is about 70%, the highest it’s ever been. From a medium term perspective, the number of jobs requiring postsecondary education is climbing. Today, just 45% of Americans have a post-secondary degree, and by 2025, 65% of jobs will require one. If you want to be in the running for that set of jobs, education beyond high school is essential. (For more information, see Lumina Foundation’sA Stronger Nation report.)At the same time, college is riskier than ever, with historic debt loads, and employers questioning the value of many postsecondary programs.So how can students handle the post-secondary paradox? Young people need to be smart shoppers about their post-secondary education. You can no longer blindly get a degree from anywhere. Some colleges do a much better job of educating and graduating students than others; plus students need to navigate a wider array of options for quality postsecondary education today. You can no longer meander across majors, without considering career goals. That’s not to say students should lock into a career path in 9th grade. Teens are not going to all of a sudden know what they will want to do in 20 years; data suggests that they change jobs even more frequently than previous generations. Students benefit when they consider careers that interest them, and the economic potential of those fields, and then thoughtfully explore them.As smart shoppers, students can consider which range of careers intrigue them, which postsecondary programs will get them on the right path, and which institutions most effectively graduate students from similar backgrounds. Unfortunately due to budget crunches, school districts are dedicating fewer and fewer resources for college and career planning. Just as the postsecondary paradox leaves students more in need of college-going know-how than ever before. Not surprisingly, college-going rates are down, especially for low-income students.

Students, parents and community organizations need to step up, help schools prioritize college and career planning, and access the resources—including influential students, recent college grads, and volunteer mentors — close at hand. (Check out: College Advising Corps, College Possible, and iMentor)The need for postsecondary education, and in fact deeper postsecondary education, becomes more pronounced the farther out we look. Some labor theorists predict we’re on the verge of the greatest workforce shift since the Industrial Revolution. Over the next few decades, large employment sectors will disappear, they say, due to automation, robotics, artificial intelligence, etc. How can we prepare for a world like that? I think we need to be skeptical of hyper-focusing on training students for what the job market requires right now. Narrowly directing students to fill today’s job gaps may lead to employment and aid certain industries in the short term, but it’s not in the service of our kids, nation or industry in the long term. Rather, we need to raise the conversation about the future of work with students, employers, education innovators, and technologists. Also, I believe it’s a smart bet that this brave new world will favor people who can lead, create, problem solve, work in teams, and persevere. We call those attributes Power Skills. These are the skills employers cite today as being most in demand. The most effective colleges develop Power Skills well, as do challenging work experiences, and demanding community service work—for example, we have seen Power Skills develop in College Summit Peer Leaders running peer campaigns in their high schools. For America to prosper relative to advancing economies around the world, we need to develop this kind of deeper learning in all students, in every corner of our nation. The question isn’t “whether” postsecondary education. It’s which kind of postsecondary education. Now is not the moment to soften ambitions, especially for students from low-income and under-represented communities climbing uphill. Nor is it time to resign ourselves to status quo postsecondary education. We need to challenge our students, educators, employers and technologists to stretch, figuring out better ways for students to learn and take charge of their future.

J.B.’s One Good Question: How can young people drive their education and improve student achievement in their communities?

J.B. Schramm chairs the Learn to Earn initiative at New Profit, a venture philanthropy and social innovation organization that provides funding and strategic support to help the most promising social innovations achieve scale. J.B. leads the organization’s ecosystem innovation work for college access, postsecondary education and career, helping colleagues in the field equip 10+M more Americans for career success by 2025.

One Good Question with Tony Monfiletto: Are the Right People in the Education Redesign Process?

This post is part of a series of interviews with international educators, policy makers, and leaders titled “One Good Question.” These interviews provide answers to my One Good Question and uncover new questions about education’s impact on the future.

“In what ways do our investments in education reveal our beliefs about the next generation’s role in the world?”

Our investment in accountability structure and high-stakes standardized testing reveals the fact that adults think of kids as problems to be solved, rather than assets to be nurtured. In Jal Mehta’s, The Allure of Order, he outlines how the investment in accountability at the back end of the system is an effort to make up for the fact that we haven’t invested as aggressively in the front end. We don’t put enough time, energy or strategy into good school design, preparation of teachers, or capital development. Because we don’t put enough resources into those areas, we try to make up for it in accountability structures.

“From substitute teacher to education policy, you’ve worked in practically every level of education impact and have deep understanding of how all of these roles influence opportunities for all students. What is standing in the way of deeper, effective collaboration for public education in this country?”

We were working off of an old industrial model of education and when that industrial model stopped getting results, we had different expectations for what schools could do, but we never changed the design of the schools to catch up to the new expectations. When we didn’t change the design of the schools or invest in the people who could populate the new generation of schools, we started accountability structures instead. If we’re going to deal with the lack of effective design, it’s going to mean dealing with both the accountability structures to make sure that it’s rethought around clear design principles. We have to do both at the same time. You can’t have accountability structures built around industrial factory schools when that model isn’t solving the problem. You have to get both right and right, but now we’re not doing either. People are trying to deal with the metrics questions but aren’t willing to give up on the design. Even those who are thinking about innovative school design, they’re still doing it within the confines of the existing model i.e. replacing teachers with blended learning. These are add-ons, not really answering questions for what’s happening in the instruction.

“Do you think we have the right people in the conversation about school design?”

I don’t. What’s happened is that we’ve let two camps develop: traditional education interest groups/educators vs. high-stakes standards educators. The traditional camp is dominated by teacher unions, school administrators, Diane Ravitch, etc. and the high-stakes camp is dominated by those who believe in econometrics. They think that if you get the econometrics right, then align the systems and create the right incentives, everything will come out in the end. The discourse on school design is dominated by those two camps and they’re not the right people to be in the conversation. The trappings of the existing system make it difficult for both camps to imagine anything else. We need youth development advocates, neuroscientists, community leaders who are not from education sector, social service providers who understand cognitive and non-cognitive human development—those are the people who ought to be in the conversations. If we had them in the discussion and designed backwards, we’d have a much differently designed school than our current models. At Leadership High School Network in Albuquerque, we operate and founded a network of schools built around 3 pillars: learning by doing, community engagement, and 360 support for kids and families. All pillars are equally important and they all hold up the institution. What we found is, when any two of the three pillars converge, the impact for kids is exponential. It’s the convergence that creates the impact, but they have to be seen as equal partners in their work in the schools.

Tony’s One Good Question: Can we give the community a new mental model for what school can look like? And then, can we create a new assessment system that allows for people to have confidence in that new model?

Tony Monfiletto is Executive Director of New Mexico Center for School Leadership. He is a father, husband, educator, visionary, thought leader, and ambitious builder of ideas and schools. He is charming, focused, intense, productive, and deeply committed to both his work, his family, and our community. Tony grew up in Albuquerque with both parents as teachers in the South Valley, family roots in northern New Mexico as well as Chicano activism and Catholic social justice as part of his life.

One Good Question with Anu Passi-Rauste: Education to Build Talent Pipelines.

This post is part of a series of interviews with international educators, policy makers, and leaders titled “One Good Question.” These interviews provide answers to my One Good Question and uncover new questions about education’s impact on the future.

“In what ways do our investments in education reveal our beliefs about the next generation’s role in the world?”

I’m really encouraged that we’re starting to see our education investments shift to include different projects and initiatives in which students are part of a bigger ecosystem and instrumental in designing our future. The new generation needs to be a part of collaboratively solving world problems. We don’t know what the jobs will be in the future because the world is changing so rapidly. I want to see the future as a sustainable world, where people are empowered to grow and learn for their own success.We see those expectations in the UN Sustainable Development Goals and on the national level in Finland. To transform our education system is a long process. Fifteen years ago, when I was a teacher, I experienced that the most fascinating way to teach was to learn together with the students. What I saw then was that, when students had problems that they were interested in, they were self motivated to dig deeper. As an entrepreneur, I have learned that the best part of my work is that I need to learn every day. We are social learners. The best part of being an entrepreneur is that we need to test all the time and validate our process. The scientific method is part of my daily life and part of my adult learning process. Education practice is slowly starting to incorporate this method into general pedagogy. The real positive inspiration is that you get interested by yourself and you start to follow some fields or topics and then identify what value you can bring there.Although we focus on skills and competence based education, those competences aren’t the only means to developing students for the future. Schools are still silos—they are physically isolated from society and within the buildings, school lessons are still divided into one-hour topics with related projects. We’re still learning for the test and valuing extrinsic motivation over instrinsic motivation. My entrepreneurial career is focused on how the school is part of the big community and creating opportunities for schools and students to work together with companies, organizations, and civic groups. Organizations can learn from the students and give students meaningful problems to solve. It also gives forerunner companies the possibility to enhance their learning about next-generation employees and consumers. As a result, students get relevant learning beyond classes, more experience and opportunities to find their own passion and motivation for learning.

“Your past projects have centered on student agency in innovation and problem-solving. What does it mean for greater society to have today's youth be an integral part of entrepreneurial solutions?”

Today’s learning is organized around problem-based learning, challenges and case studies. What if this could be done in close collaboration in our actual economic ecosystem ? If we can bridge this gap, it helps us to employ the young graduates and build their courage, self confidence, and attitude for lifelong learning and self trust. We can create opportunities for students to feel integrated and valuable in greater society. We help students with their ideas and have industry experts who are willing to listen and coach them. In the end, students come up with brilliant solutions to company-based challenges or their own ideas for start-ups. This model also increases democratic opportunities for the broader population.One thing that I’ve learned is that, when students are really working on their own ideas, they want to be responsible for their own learning. It doesn’t mean that they don’t need support, but that they can then identify the supports that they need. That’s what creates a critical role for teachers, facilitators and companies to respond to the students’ needs. Access to community-supported learning needs to be a right for everybody. We still have work to do to refine the models that connect the employers and students. Under our new venture, LearnBrand, we want to give students an opportunity to apply the knowledge that they’ve learned, which is a critical part of the learning process. We focus on actionable learning where we engage people during their college and university studies. We give them real world assignments and experience. We build a bridge between learners and employers and help both sides equally; students grow their practical skills and employers manage their future talent pipeline.

Anu’s One Good Question : How do we empower our students to keep their curiousity and growth mindset throughout their lives ?

Anu Passi-Rauste, an avant-garde educator and leading expert in digital learning, challenges educators, students, and policymakers to adopt innovative approaches to education in K-12, higher education, and corporate training settings. Her latest venture, LearnBrand, strengthens business partnerships for college and university students.

The Year in Review: 10 Good Questions.

Asking the right questions is more important than having the right answers. One of my favorite parts of the fall interviews was to hear these amazingly accomplished, visionary thinkers and doers ask questions that they couldn't answer on their own. Looking forward to hearing more questions in the new year.

1. Zaki’s One Good Question : Bangladesh has made lots of progress to educate more people in our society, but we see that the system is not yet producing a respectful society. Education is about creating global peace. Are we matching what we really want to accomplish through education ? Are we missing the way that education should be defined ? (BL)

2. Saku’s One Good Question : My question is an extremely boring one: What is the point of school ? Once we answer that, then we can move on to the question of how to educate all youth. (FI)

3. Michael’s One Good Question : How much input should local, state, and federal governments have on the programmatic strategies of schools, given their variation in education goals and knowledge of effective programs ? (US)

4. Noëlle’s One Good Question : How well does our education system engage students? Ideally, I would specify "boys" rather than just "students" because boys are falling behind in Malaysia. Girls outperform boys in Maths and Science unlike international norms. And in public universities, girls account for 70% of the intake. Our education blueprint has highlighted the risk of "lost boys". It appears our education system isn't really working out for boys. Given the patriarchal expectations within conservative communities, I wonder what impact this achievement gap will have on the next generation. (MY)